Introduction

High-resolution ultrasonography (US), being one of the most sensitive imaging techniques, is used to describe the number, size, and topography of thyroid nodules with respect to their glandular architecture. It is recommended as the first line diagnostic tool by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the European Thyroid Association [1]. The introduction of standardised risk stratifications called the Thyroid Imaging Reporting & Data System (TIRADS), a grading method to classify thyroid nodules, aims to reduce the need for more invasive and costly tests [2]. TIRADS assists in identifying the likelihood of nodule malignancy based on its composition, echogenicity, shape, margin, and echogenic foci, with higher scoring nodules more likely to be malignant. Studies report that effective implementation of TIRADS could eliminate over half of currently required fine-needle aspiration biopsies (FNAB), which, apart from increased costs, carry a risk of complications and stress for the patient [3,4]. The three most commonly used versions of TIRADS are the American College of Radiology ACR TIRADS, the European EU-TIRADS and the Korean KTIRADS. The classifications differ in criteria of high-risk features and indications for FNAB. Whilst the ACR TIRADS has been proven to be most accurate, all methods have demonstrated high effectiveness in reducing the necessity of FNAB, with an accuracy of over 80% [5].

The TIRADS grading has been incorporated into the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and European Thyroid Association guidelines (EU-TIRADS) [6]. However, such grading has only recently been adopted by the Polish Society of Ultrasonography in its guidelines for diagnosis of thyroid carcinoma [7]. Despite positive outcomes, implementation of TIRADS in clinical practice is limited. Mauri et al., who examined the knowledge and use of TIRADS in Italy, found that only 53.6% of respondents were familiar with the classification, of whom 45.9% used TIRADS in their regular practice [8].

This pilot study aimed to examine the knowledge and utilisation of the TIRADS classification amongst Polish physicians in their everyday clinical practice. Furthermore, it explored the use of different TIRADS versions, the perception of the clinical usefulness of TIRADS and the extent of knowledge of individual nodule features included in the scoring system.

Material and methods

Study design

An internet-based, anonymous questionnaire regarding the respondent’s knowledge and application of TIRADS in clinical practice was provided to the Secretary of the Polish Ultrasound Society, who approved and forwarded it to all society members. A cover letter accompanying the survey provided a brief overview of the research purpose and information about optional participation. Additionally, the respondents were informed that the data were being collected and analysed anonymously.

The approval of the bioethics committee was not required. The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration, its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. It was assumed that all responders provided informed consent.

Data collection

The survey collected information regarding age, gender, specialty (radiology or other), ultrasonography as a main clinical activity (yes or no), annual number of sonography sessions (0 – none performed, ≤ 100, > 100), performing or assisting with FNAB (yes or no), place of work (university, other hospital (e.g. district), combination), catchment area. Additionally, questions related to TIRADS were also included, such as familiarity with TIRADS (yes or no), type of TIRADS used (ACR, EU, do not use at all), which imaging features are included in TIRADS and the respondent’s opinion on why particular features were included in the TIRADS classification. For the last two items more than one answer could be provided and the combination of multiple items was allowed.

As the current study was a pilot study of descriptive nature, the experiment did not lend itself to a power analysis for projected sample size, and a goal of 100 respondents was set as a minimum. The survey was collected in the period from December 2021 to May 2022.

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to assess normality of distribution. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of categorical variables and reported in percentages. Continuous variables were analysed with the Mann-Whitney U test and reported as medians and interquartile ranges. Comparisons were considered significant if the two-tailed p-value was less than 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0.

Results

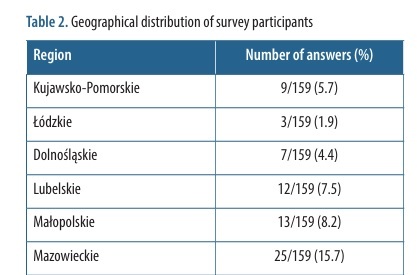

A total of 159 physicians completed the survey, which equals 23% of the total number of Polish Ultrasound Society members. The questionnaire answers are summarized in Table 1. The median (interquartile range) age of the respondents was 41 (32-55) years. Females constituted slightly over half of the participants (50.9%). The TIRADS classification systems were utilized by 33.3% of respondents, with the EU-TIRADS being the most frequently adopted (50.9% of users). The majority of responders did not use TIRADS (66.6%) despite their awareness of its existence (43.4%). Data summarizing the regional distribution of survey participants are presented in Table 2.

Table 1

List of questions and answers in the online survey

Table 2

Geographical distribution of survey participants

The differences between physicians who used and did not use the TIRADS classification are presented in Table 3. Participants who adopted TIRADS were 7 years younger with a median age of 38 years (p = 0.047). Radiologists were significantly more prone to follow the classification compared to physicians of other specialties (p < 0.01). The TIRADS classification was also more widely used in university clinical hospitals compared to other centres (p = 0.02). Physicians who were conducting thyroid ultrasound as their primary professional activity (p < 0.01), those performing > 100 thyroid ultrasound examinations per year (p < 0.01) and those involved with thyroid FNAB (p < 0.01) reported significantly higher utilization of the TIRADS classifications compared to their counterparts. Physicians who used the TIRADS classification responded more accurately when inquired about the purpose of TIRADS compared to those who did not utilize it (p < 0.01). All the image features included in TIRADS (composition of lesion, echogenicity of lesion, margin of lesion, shape of lesion, calcifications) were also identified more accurately by participants adopting the classification (p < 0.01).

Table 3

Data analysis grouped according to answers to question #9 of the survey

Discussion

Our findings reveal significant variability in TIRADS implementation among the Polish Ultrasound Society members dealing with thyroid nodules. While 33.3% of respondents utilise TIRADS, a significant proportion (43.4%) reported that they did not use it, despite being aware of the classification’s existence. The reasons for such outcomes may include the availability of resources, hospital policies, amount of time allocated per patient or variations in training. A large proportion of physicians who employ TIRADS guidelines in Poland work in university clinical hospitals. This is not surprising, as research shows that teaching and university hospitals provide a better level of care through efficient implementation of novel, evidence-based methods of treatment [9,10]. Furthermore, the TIRADS classification was more frequently utilised by physicians working in the economically stronger regions such as the Silesian, Pomeranian and Masovian voivodeships. Those regions encompass major Polish cities including Katowice, Gdansk and Warsaw and show high gross domestic product contributions compared to other voivodeships [11].

Interestingly, radiologists apply TIRADS more frequently in their practice compared to physicians of other specialties. This finding is contradictory to recent research conducted in Italy, which showed a higher prevalence of TIRADS use among specialists other than radiologists [8]. Additionally, a significant proportion of TIRADS users were those who performed a high number of thyroid US examinations – over 100 per year and performing these as their primary professional activity. Moreover, TIRADS use was associated with performing FNAB. As many TIRADS users work in university clinical hospitals committed to evidence-based practice, which likely have higher admission rates, those physicians perform US examinations more frequently. In such busy practices, physicians often share responsibilities, and thus may be more likely to standardise their patient approach in order to improve inter-observer agreement and multidisciplinary work efficiency [12,13]. Therefore, those working in university clinical hospitals are more likely to recognise the time- and cost-effectiveness of TIRADS [2]. Studies have shown TIRADS implementation has proven successful in reducing the number of currently required FNAB by 52.6% [3,14], thereby saving time and resources and minimising unnecessary patient discomfort and anxiety. Nonetheless, a significant number of physicians, particularly those working in district general hospitals and other regional healthcare facilities, still do not use TIRADS. In those facilities TIRADS implementation should be especially encouraged.

When inquired about the purpose of TIRADS, the most frequent response, chosen by 89% of respondents using TIRADS, was to predict pathological changes within the thyroid found in FNAB. Other commonly chosen answers were the standardisation of US descriptions (81%) and optimisation of FNAB costs (51%). Additionally, 36% of users thought the purpose of TIRADS was to increase detection of thyroid cancers. Unsurprisingly, physicians familiar with the classification are aware that TIRADS can help better identify potentially malignant nodules but is not a diagnostic tool by itself.

Participants were asked to indicate imaging features which they thought are present in TIRADS. Statistically, TIRADS users were more aware of these features, but a significant number also chose the option of lesion vascularity. Size of the lesion was chosen by 57% of TIRADS-using respondents. According to the Polish Recommendations for Diagnostics and Treatment of Thyroid Cancer [15], lesion size is an essential element to be considered when deciding between follow-up or FNAB, although it is not a TIRADS feature itself. The newly revised Polish guidelines are stricter with regards to nodule size eligible for FNAB [15]. In contrast to the original EU-TIRADS, the EU-TIRADS-PL recommends FNAB for high-risk nodules > 5 mm instead of > 10 mm [6,15]. All the features of TIRADS were successfully chosen by over 92% of TIRADS users. These findings suggest that the overall knowledge of TIRADS components among practising clinicians is satisfactory, with only minor room for improvement.

The small number of responses received from the Polish Ultrasound Society members posed a considerable limitation to our study. Despite the guarantee of confidentiality and anonymity, the participation rate was only moderate. Moreover, physicians who are either unfamiliar with TIRADS or do not routinely incorporate it into their daily practice may have opted not to participate in our survey, which might have introduced a selection bias, further limiting the generalisation of the gathered data.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrates that the application of TIRADS among members of the Polish Ultrasound Society is not satisfactory. There is a clear need for further training and widespread adoption of TIRADS. Further research should be aimed at better understanding the barriers to TIRADS implementation and later explore the long-term outcomes of its use. Hopefully, introduction of the new EU-TIRADS-PL recommendations will improve standardised reporting.