Introduction

Skull base osteomyelitis (SBO), although an uncommon clinical entity, poses a significant challenge to most clinicians because of its unpredictable clinical course and often lethal nature. The disease is often seen in conjunction with aggressive infectious pathologies of the head and neck; mainly otitis media, otitis externa, and rhinosinusitis [1]. These often progress in patients with underlying risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus and immunosuppression. However, the clinical presentation is in itself non-specific, with a myriad of signs and symptoms including headache, orbital congestion, and cranial nerve palsies [2]. Therefore, imaging remains the mainstay of diagnosis and prognostication of this sinister complication.

Bacteria (predominantly Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus) [1] and fungi of the Aspergillus sp. [3] and Mucorales (Rhizopus and Mucor spp.) [4] have emerged as the foremost aetiological agents for SBO, although anecdotal reports of several other organisms exist. Multiple investigators have highlighted differences in the management strategy amongst the 2 groups, with fungal SBO requiring surgical intervention in addition to the obvious variation in antimicrobial therapy for both groups [5]. In addition, even among the fungal species, it has been observed that Mucorales (Mucor) have a far more fulminant course, higher instance of complications, and need for surgical debridement, in comparison to the Aspergillus sp. [6]. It becomes imperative, therefore, to provide an imaging-based aetiological classification to aid in management. This is particularly important because surgical biopsy is often not feasible due to the anatomical complexity of this region, as well as low patient tolerance. The positivity rates of microbial cultures are also low [7].

While several authors have reported varying presentations of both fungal as well as bacterial SBO, these exist mostly as isolated case reports. Only a few series involving large patient subsets exist in the literature. There is also a paucity of studies comparing the different presentations or imaging features of the culprit organisms. We aim to address these issues by evaluating the reported clinical, as well as radiological, parameters of the index studies in cases of SBO.

Material and methods

This systematic review was conducted as per the PRISMA guidelines [8].

Eligibility criteria

The studies were required to fulfil the following criteria to be considered for this systematic review: 1) imaging features on at least 1 cross-sectional imaging modality (either CT or MRI) reported; 2) inclusion of clinical parameters including underlying immunosuppression, presenting complaints and/or treatment strategy, mortality, etc.; 3) full text of article available in English language; and 4) exclusion of review articles, case reports, pictorial essays, and letters to the editor.

Information sources

The PubMed and Google Scholar databases were searched in April 2020 for studies which satisfied the eligibility criteria. The keywords used were: ‘skull base osteomyelitis’ or ‘skull base’ AND ‘radiology’ or ‘imaging’ AND ‘fungal’ or ‘bacterial’. The title as well as abstracts of the studies were examined by reviewers for inclusion in the study. The identified articles were retrieved, and a manual search of bibliography was done to identify other potentially relevant studies. Following this, the search keywords were expanded to include ‘rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis’ or ‘craniocerebral aspergillosis’ AND ‘imaging’ or ‘MRI’ or ‘magnetic resonance imaging’. An additional search of Embase was done using the same keywords as above.

Final study selection

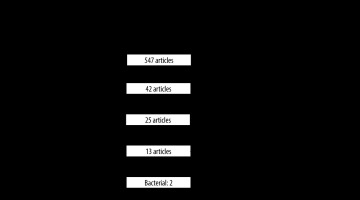

Using these search criteria, initially 547 articles were identified. We excluded duplicate articles, review articles, case reports, pictorial essays, and letters to the editor. We also excluded articles that did not give details of radiological parameters assessed and those in which the full text could not be obtained despite our best efforts. It was also decided to exclude case series with less than 10 patients, because we felt these were not truly representative. We also excluded articles that reported only intracerebral aspergillosis, because this differed from our primary aim of describing SBO imaging findings.

Data extraction

We examined the included studies for study design, participants, and imaging modalities used. A data extraction form was used to grade the level of evidence and bias by 2 radiologists. Disputes were settled through consensus approach. The level of evidence was graded using the guidelines for diagnostic tests by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [9]. The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 (QUADAS-2) tool [10] was used to determine risk of bias and concerns of applicability.

Following this, we entered all relevant clinical and radiological parameters of the studies in the form. Clinical parameters assessed included the mean age/age range of participants, predisposing conditions causing immune compromise, patient presentation, treatment strategy used, and mortality. Imaging parameters detailed include- site of initial infection, bone erosion, orbital extension, intracranial extension, vascular complications and any other relevant findings including deep extension, enhancement patterns, and MRI signal characteristics. If a study was limited to a certain subset of patients (e.g. orbital disease only) and extension to other subsites was not detailed, the remaining parameters were not described. However, if the study did not describe any such subsite limitation but information on certain parameters (e.g. orbital extension) was missing, it was assumed as being absent and we labelled it as ‘not reported’. Due to the heterogeneity of data and lack of complete information in both clinical and imaging data, we did not attempt a meta-analysis.

Results

Literature search and study selection

Using the search criteria, initially 547 articles were identified. After screening titles and abstracts and removing duplicate articles, we shortlisted 42 articles. Of these, we could not find the full text of 3 articles in English language despite our best attempts. The full text of 39 articles was scanned by 2 radiologists. Of these, 14 articles did not describe cross-sectional imaging findings, another 4 had sample size of less than 10, and 8 dealt only with allergic fungal rhinosinusitis or intracerebral aspergillosis. Finally, 13 articles were selected for the study. Of these, 9 reported fungal SBO [2,11-18], 2 reported bacterial SBO [7,19], and another 2 had patients with both organisms [20,21]. The search methodology is detailed in Figure 1.

QUADAS 2 assessment

The details of studies included are provided in Table 1. The study design, number of patients, and level of evidence is detailed. The risk of bias and applicability concerns are also mentioned. Overall, 12 studies had risk of bias. The chief domain among bias risk was the patient selection and interpretation of index test results, due to the retrospective design of the studies. The patient selection was not consecutive/random, and the results of reference standard were available to interpreting diagnosticians. None of the studies had bias in the reference standard.

Table 1

Details of studies included with QUADAS-2 assessment

| Year, country | Author | Study design | Number of patients | Imaging modality | Level of evidence | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Aspergillus | Mucor | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | |||||

| 2019 Czech | Mejzlik et al. [7] | R | 21 | – | – | CT + MRI | 3 | + | +/– | – | – | + | – |

| 2018 India | Therakathu et al. [2] | R | – | – | 43 | CT + MRI | 3 | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| 2016 Korea | Son et al. [20] | R | 14 | – | 20 | CT | 4 | + | +/– | – | – | – | +/– |

| 2015 Turkey | Kursun et al. [18] | R | – | – | 28 | CT ± MRI | 3 | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| 2014 Paris | Le Clerc et al. [21] | R | 28 | 3 | – | CT/MRI | 4/2 | +/– | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2014 India | Prasad et al. [19] | P | 16 | – | – | CT | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2006 Pakistan | Siddiqui et al. [12] | R | – | 20 | – | MRI | 3 | + | + | – | – | +/– | – |

| 2004 Pakistan | Siddiqui et al. [11] | R | – | 25 | – | CT ± MRI | 3 | + | + | – | – | +/– | – |

| 2004 India | Mohindra et al. [13] | R | – | – | 27 | CT ± MRI | 3 | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| 2002 Israel | Talmi et al. [14] | R | – | – | 19 | CT ± MRI | 3 | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| 2001 India | Murthy et al. [15] | R | – | 16 | – | CT | 3 | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| 1986 USA | Gamba et al. [16] | R | – | – | 10 | CT | 3 | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| 1981 USA | Centeno et al. [17] | R | – | 2 | 10 | CT | 3 | + | + | – | – | – | – |

Clinical parameters

The clinical details extracted from the studies are listed in Table 2. A wide age range was seen among studies reporting both bacterial as well as fungal aetiologies. However, we observed that there was relative sparing of the paediatric population, with only 3/13 studies reporting inclusion of children less than 5 years old (1 from the bacterial group [19] and 2 from the Mucor group [2,13]). 3/13 studies had immune-competent patients in varying numbers [11-13], while the rest had only immune-compromised patients. Of these, 2 studies with Aspergillus SBO recruited only immune-competent patients [11,12]. The most consistent predisposing factor among the 11/13 studies who had patients with some degree of immune compromise was diabetes mellitus, present in proportions ranging from 12.5 to 91%, with highest proportions reported in the Mucor study groups (21-91%) [2,13,16,18,20]. Others included haematological disorders, steroid use, and immunosuppressive drugs.

Among all the studies reporting purely bacterial aetiology SBO, the presenting complaints were otogenic [7,19,21], while among the studies reporting purely fungal aetiology, complaints varied and included headache, nasal discharge/stuffiness, and ocular symptoms such as pain or ophthalmoplegia [2,11,12,14-18]. One of the studies dealt only with orbital manifestations and therefore reported ocular complaints in 100% of patients [20]. The characteristic black necrotic lesions or ‘eschar’ was seen in 3/13 studies, of which all had patients with Mucor SBO [13,14,17]. On comparison of incidence of cranial nerve palsies amongst groups, studies with bacterial SBO reported 33-100% incidence [7,19,21], while those with Mucor SBO and Aspergillus SBO reported 10-83% [2,13,16,17] and approximately 18-30% [11,12,15], respectively.

In terms of the management strategy used, the rates for surgical intervention in bacterial SBO were between 7 and 87% [19,21], while those in fungal SBO were higher, ranging from 50 to 100% [11,13-18]. Antimicrobial strategy for fungal SBO caused by Aspergillus sp. involved the use of oral triazole therapy for 5-7 months in addition to the initial use of Amphotericin B intravenously, or even oral therapy in isolation when no intracranial extension was present [11,12,21]. For Mucor, antifungal therapy consisted of intravenous Amphotericin B only, with liposomal form used in the newer study [18]. Hyperbaric oxygen was used in only 2 of the studies [16,19]. The mortality rates were also different for both groups. Fungal SBO had higher mortality, particularly amongst patients who did not undergo surgery and those who had intracranial extension. The rates were as high as 50% in 4 studies [14,16-18], while for bacterial SBO the maximum mortality was close to 10% [7].

Table 2

Clinical details of patients in included studies

| Criteria | Mean age (range) in years | Predisposing factors | Presentation | Treatment | Mortality | Cranial nerve palsy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mejzlik [7] | 78 | DM: 50.0% Renal failure: 33.3% Pulmonary disease: 33.3% | EAC infection: 100.0% | Systemic antibiotics based on C/S ± mastoidectomy (based on clinical/CT features) | 2 (9.5%) | 100% VIII: 58.3% VII: 50% Others: IX-XII | |

| Therakathu [2] | 55 (2-75) | DM: 91% Haematological: 9.3% | Headache: 88% Nasal discharge: 69% Facial swelling: 69% | – | – | 25% | |

| Son [20] | |||||||

| Mucor | 63.2 ± 10.9 | DM: 71.4% HTN: 57.1% Others: 28.6% | EOM movement limitation: 100% Chemosis: 60.0% Ptosis: 57.1% | – | – | – | |

| Bacterial | 47.1 ± 22.9 | DM: 5.0% HTN: 20.0% Others: 5.0% | Eyelid swelling: 90.0% Chemosis: 85.0% EOM limitation: 66.7% | – | – | – | |

| Kursun [18] | 53.2 (12-81) | DM: 50.0% Steroid: 21.0% Haematological: 14.0% | Fever: 79.0% Peri-orbital cellulitis: 75.0% Headache: 71.0% | Liposomal Amp B Surgery (100%) | 14 (50%) | – | |

| Le Clerc [21] | – | DM | Otalgia: 83.0% Otorrhea: 83.0% | Nil | 47% (CN VII) | ||

| Aspergillus | 45 ± 39 days IV, 5-7 m oral (voriconazole, posaconazole) Surgery (33.3%) | – | 3/3 | ||||

| Bacteria | CFR: 138 ± 81 days CFS: 17 ± 10 Surgery (7.1%) | – | CFR: 5/5 CFS: 5/15 | ||||

| Prasad [19] | 2-68 | DM (56%) | Otorrhea, granulations: 100% Otalgia: 85% | Systemic antibiotics (ciprofloxacin) Surgery (87%) Hyperbaric oxygen (5%) | Nil | 35% (CN VII) | |

| Siddiqui [12] | 31.1 (14-74) | Immune competent | 3(15%) | 30% | |||

| Type 1* | Headache, papilledema, CN deficit, convulsions | Surgery (100%) | 3 (50%) | ||||

| Type 2* | Headache, nasal stuffiness, discharge, loss of vision, impaired consciousness | IV Amp B + oral itraconazole | Nil | ||||

| Type 3* | Nasal stuffiness, discharge, diplopia, visual loss | Oral itraconazole | Nil | ||||

| Siddiqui [11] | 36.5 (14-74) | Immune competent | Nasal stuffiness: 52.0% Headache: 40.0% Proptosis: 36.0% | Oral itraconazole ± IV Amp B (if intracranial extension) Surgery (100%) | 7 (28%) Type I: 66.7% Type II: 25% | 24% | |

| Mohindra [13] | 41.7 (2.5-71) | DM: 59.3% Immune suppressive drugs: 11.1% Immune competent: 23.1% | Ocular complaints (proptosis, blindness, diplopia, pain): 77.8% Altered sensorium: 37.0% Eschar: 14.8% | Amp B Surgery (85.2%) | 29.6% (includes 4 patients not operated) | 74.1% II, III, IV > VI > V | |

| Murthy [15] | 41.8 (19-65) | DM: 12.5% | CS syndrome: 31.3% Ocular complaints (proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, OAS): 31.3% | Amp B Surgery (100%) | 31.3% | 18.8% | |

| Talmi [14] | 60 (34-87) | Haematological: 63.2% DM: 21.1% | Eschar: 94.7% Ocular complaints (chemosis, proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, loss of vision): 79% Nasal discharge: 73.7% | Amp B Surgery (63.2%) | 52.6% (includes 7 patients not operated) | Present | |

| Gamba [16] | 57.2 (32-80) | DM: 90% | Ocular complaints (proptosis, chemosis, visual loss): 70% Headache: 40% | Amp B Surgery (90%) Hyperbaric oxygen (50%) | 50% | 10% (CN VII) | |

| Centeno [17] | 18-75 | DM: 75.0% Steroid: 8.3% Haematological: 8.3% | Necrotic oral/nasal lesions: 75.0% Facial pain: 66.7% Ophthalmoplegia: 50.0% | Amp B Surgery (100%) | 6 (50%) Aspergillus: 2 (100%) Mucor: 4 (40%) | 83.3% III, IV, V1, V2, VI: 58.3% VII-X: 25% | |

Imaging parameters

The details of imaging features extracted from the studies are listed in Table 3. There was a clear predilection regarding the predominant site of involvement, with bacterial aetiology favouring otogenic involvement – most commonly the EAC but also the middle ear. Fungal aetiology, on the other hand, showed a predominant paranasal sinus (PNS) involvement. This involvement was commonly in the form of mucosal thickening in sinuses, as reported in 5 studies of fungal SBO [2,12,16,18,20]. Ethmoid sinus was most frequently affected in 3 of these studies [2,13,15], while maxillary sinus was the favoured site in 1 study [16]. The reported incidence of orbital involvement in bacterial SBO was < 5% [7], whereas fungal SBO showed orbital extension in the range of 44-76% [2,13,15-18]. There was a greater incidence of orbital extension in Mucor SBO, with most studies reporting 65-70% involvement [2,14,16-18]. Half of the studies with fungal SBO used a classification system based on extension of disease; wherein subsites of involvement (sinus, orbit, cranium, deep tissues) were considered [2,11-13,15,18]. It was observed that Aspergillus studies showed a higher proportion of patients with sino-cranial extension of disease [11,12,15], while Mucor studies showed greater preponderance of sino-orbital or sino-orbito-cranial forms [2,13,18].

Table 3

Radiological details of patients in included studies

| Criteria | Site | Orbital extension | SBO clinico-radiological form | Bone erosion | Intracranial complications | Vascular complications | Other findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAC | PNS | Vein | Artery | |||||||

| Mejzlik [7] | + | – | I/L upper eyelid: 4.7% | – | Late - Temporal bone destruction - T1 hypointensity in clivus | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Adjacent to stylomastoid foramen Pharyngobasilar fascia- frontal boundary | |

| Therakathu [2] | – | + | 76% Orbital apex: 50% | Sino-orbito-cranial (58.1%) Sino-orbital (37.3%) Sinus (4.7%) | Present: 40% Rarefaction, erosion, permeative destruction Chronic: 11.6% Expansion, sclerosis, lytic destruction, erosion | 31% Cerebritis: 6.9%, Infarcts: 9.3% Intracranial abscess: 4.7% Epidural abscess: 4.7% | 14% (CS) | 10% (ICA) | PPF extension: 48% Enhancement pattern CT Mild enh: 70% Non enh: 23% MRI Heterogenous enh: 36% Central non enh ± rim enh: 36% Homogenous enh: 29% T1 hypointense: 100% T2 hypointense: 37% | |

| Son [20] | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bacteria | 45% | |||||||||

| Mucor | 92.90% | |||||||||

| Kursun [18] | – | + | Peri-orbital muscle inflammation: 69% | Rhino-orbital (44.4%) Nasal (28.5%) Rhino-orbito-cerebral (25.0%) | – | Infarction: 19% | 27% (CS) | 11% (ICA) | – | |

| Le Clerc [21] | + | – | Not reported | – | Present: 100% Extent Bacterial: less Fungal: more | Not reported | Not reported | – | – | |

| Prasad [19] | + Middle ear and mastoid | – | Not reported | Acute OM: 10% Chronic OM: 80% | Cortical bone erosion: 100% Bony sequestra: 76% | Meningitis: 1 | Not reported | – | – | |

| Siddiqui [12] | – | + | Present | Sinus walls/ cranial base-85% | 4% (CS) | – | Calcification (15%) | |||

| Type I* | Sino-cranial: 55% | 30% | ||||||||

| Type II* | – | 25% | ||||||||

| Type III* | Sino-orbital: 45% | – | ||||||||

| Siddiqui [11] | – | + | Present | Sinus walls/cranial base: 68% | Not reported | – | Calcification (12%) MRI: Extremely T2 hypointense (95%) T1 iso-hypointense Homogenous bright enh | |||

| Type I* | Sino-cranial- 52% | 36% | ||||||||

| Type II* | – | 16% | ||||||||

| Type III* | Sino-orbital- 48% | – | ||||||||

| Mohindra [13] | – | + 81.40% | 74.10% | Sino-orbital: 44.4% Sinusoidal: 18.5% Sino-orbito-cranial: 11.1% | – | Intracranial mass: 11.1% Abscess: 7.4% Infarction: 7.4% | 11.1% (CS) | – | – | |

| Murthy [15] | – | + | 43.80% | Sino-cranial (56.3%) Sino-orbito-cranial (25%) Sino-orbital (12.5%) | Present | Intracranial mass: 81.3% Meningeal enh: 6.3% | – | – | Homogenous/heterogenous enh | |

| Talmi [14] | – | + | – | Chronic form: 21.10% | Nil | Abscess/cerebritis: 10.4% | 5.3% (CS) 5.3% (SOV) | – | – | |

| Gamba [16] | – | + (90%) | 60% | – | Present: 20% | Abscess: 30% Infarct: 50% Meningeal enh: 10% | 10% (CS) 10% (SOV) | – | 50% ITF 60% PPF | |

| Centeno [17] | – | + | 66.70% a) MR lateral displacement: 25% b) MR + ON involvement: 41.7% | – | Present: 25% | Abscess: 16.7% Infarction: 8.3% | Asp 2/2 (CS) Mucor 2/2 (CS) 1/1 (IJV) | 2/2 (ICA) 1/1 (ICA) | – | |

[i] EAC – external auditory canal, PNS – paranasal sinus, CS – cavernous sinus, Enh – enhancement, ICA – internal carotid artery, SOV – superior ophthalmic vein, HCP – hydrocephalus, IJV – internal jugular vein, OM – osteomyelitis, MR – medial rectus, ON – optic nerve, PPF – pterygopalatine fossa, ITF – infratemporal fossa. *Type I – intracerebral extension, Type II – intracranial extradural extension, Type III – skull base/orbital invasion only

Bone erosion was seen among 5/9 studies on fungal SBO, with incidence ranging from 25% to 85% [2,11,12,16,17]. Three studies on bacterial SBO also reported the presence of erosions. It was described as a late finding in one of these [7], while another one described lesser extent of erosions in comparison to fungal SBO [21].

Vascular involvement and intracranial complications were both widespread in fungal SBO, whereas only anecdotal reports of these complications were seen in bacterial SBO. Amongst the intracranial complications, dural-based intracranial masses were seen more frequently in Aspergillus sp. [11,12,15], whereas Mucor had higher incidence of brain abscess or infarct [2,14,16-18]. Vascular complications were also seen more frequently in Mucor patients, with cavernous sinus thrombosis being the most frequent finding [2,13,14,16,17]. Superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis was seen in 2 studies of Mucor SBO [14,16]. Another relevant finding to note was the enhancement characteristics of the lesions. Mucor had a higher incidence of mild or non-enhancing mucosa on CT (> 90%) and heterogenous enhancement on MRI [2]. Aspergillus, on the other hand, showed homogenous bright enhancement in some studies, and mixed enhancement in the others [12,15]. MRI signal was detailed in 2 studies on fungal SBO. Both of these showed T1 and T2 hypointensity of the fungal lesions in varying numbers ranging from 35 to 100% [2,11].

Discussion

We performed this study with a view to differentiate between the clinical as well as cross-sectional imaging features of bacterial, Aspergillus, and Mucor SBO. A geographical trend of incidence was observed in our study, whereby most studies (reporting fungal SBO in particular) were from East Asia. A tropical climate has been reported to increase the incidence of Aspergillus SBO in immune-competent hosts [22].

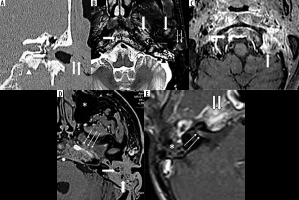

Bacterial SBO is usually secondary to malignant otitis externa, leading to osteomyelitis of the temporal bone, which spreads across the tympanomastoid suture to affect the central skull base [7] (Figure 2). Mucorales SBO, on the other hand, is caused by inhalation of spores of the organism, which become pathogenic and invasive in immunocompromised individuals. Aspergillus is also a frequent contaminant of the nasal cavity, and it may exist both in invasive and non-invasive forms. The impetus for saprophytic Aspergillus to become pathogenic may be provided by chronic obstruction of the nose or PNS [23]. However, in addition to this, there is a significant proportion of craniocerebral aspergillosis that may be caused by haematogenous dissemination from the more common manifestation of invasive aspergillosis, i.e. pulmonary infections. Thus, in keeping with the pathophysiology, bacterial SBO showed predominantly otogenic involvement, while fungal SBO presented with a wider range of nasal/ocular complaints. The incidence of cranial neuropathies was similar in both groups, but the patterns differed. Because bacterial SBO tends to spread from the temporal bone inwards, there was a higher incidence of palsy of facial nerves (CN VII) in the initial presentation, with later involvement of CNs VIII-XII (Figure 2E). On the other hand, since fungal SBO spreads from PNS upwards and also tends to involve the cavernous sinus, there was a greater incidence of palsies of CNs III, IV, V1, V2, and VI. Bacterial SBO showed good clinical response to antibiotics. Mastoidectomy was required only in cases with extensive disease on imaging or in those with clinical progression despite antibiotic therapy. Fungal SBO, however, showed an aggressive clinical course in both immune-competent and -compromised patients, with higher requirements of surgical intervention and mortality. It was also seen that the clinical course of Mucor was more fulminant with greater mortality and morbidity than Aspergillus.

Figure 2

Bacterial skull base osteomyelitis (SBO). A-C) 62-year-old male with bacterial SBO. A) Coronal unenhanced computed tomography (CT) shows soft tissue in the left external auditory canal (solid arrow) as well as the middle ear cavity (arrow). The inferior aspect of the petrous apex shows irregularity (arrowhead). B) Axial T2 FS MR shows T2 hyperintense soft tissue in the EAC (arrows), corresponding to the CT. Mastoid air cells are also fluid filled (arrowhead). T2 hyperintensity in the petrous apex, clivus and mandibular condyle (solid arrows) suggests marrow edema. C) T1 FS post gad image shows enhancement in the clivus and the jugular fossa (solid arrows). D) 54-year-old female with bacterial SBO. Axial T1 FS post gad MR shows enhancing soft tissue involving the EAC, middle ear cavity and mastoid (solid arrows). Enhancing soft tissue is also at the petrous apex encasing the left internal carotid artery (arrows), which however shows normal calibre. Note the clear paranasal sinuses (*). E) 23-year-old female with chronic otitis media complicated by SBO. Axial T1 post gad image shows enhancement of the petrous apex (solid arrows) and the vestibulocochlear nerve complex in the internal auditory canal (arrows). Note the opacification of middle ear and mastoid air cells (*)

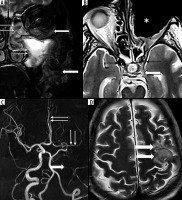

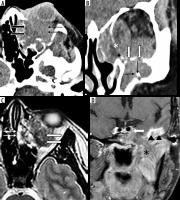

The difference in clinical predilection was also reflected in the imaging findings, with bacterial SBO showing predominant involvement of the EAC, along with the middle ear or mastoid air cells occasionally (Figure 2A, B, D). Similarly, disease extension into deep tissues was also seen to differ among the groups. While bacterial SBO was limited anteriorly by the pharyngobasilar fascia, the spread of fungal SBO was seen further anteriorly, predominantly into the pterygopalatine fossa and subcutaneous tissue of cheek and face region (Figure 3A). Ethmoid sinus was the most frequently affected among the paranasal sinuses, by both Aspergillus and Mucor. Mucosal thickening was seen more commonly than complete opacification or air-fluid levels, probably because of the early spread of fungal disease and hence early presentation with overt patient symptoms. The path of least resistance for further spread of infection lies across the lamina papyracea to the orbit, followed by the orbital apex and then to the cavernous sinus, which is responsible for the corresponding clinical and radiological manifestations of orbital, cavernous sinus and cavernous ICA involvement [2] (Figure 3B, C, D). This lends itself to a natural classification, whereby increasing severity is indicated by rhinosinusitis, sino-orbital, and sino-orbito-cranial forms [24] (Figure 4A, B, C). However, there have been reports of Aspergillus migrating across the cribriform plate directly into the anterior cranial fossa. The postulated mechanism for this is migration along the perivascular spaces and spread from the PNS even without frank bony destruction [23]. Thus, there was higher incidence of sino-cranial spread in Aspergillus SBO, with many reporting seemingly non-contiguous extra-axial intracranial masses (Figure 4D).

Figure 3

54-year-old female with rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis. A) Coronal T2 FS MR shows the mucosal thickening in the left maxillary and ethmoid sinuses (arrows). T2 hyperintensity and fat stranding is seen in the orbit and deep tissues (solid arrow). B) Post-operative axial T2 WI shows dural thickening with convexity in the left cavernous sinus (solid arrow). The left cavernous ICA flow void is not visualised, compared with right cavernous ICA (arrows). Patient had undergone maxillectomy, ethmoidectomy and orbital exenteration (*). C) TOF MRA maximum intensity projection shows non visualization of the left ICA (solid arrow) and narrowing of the left ACA and MCA with paucity of their distal branches (arrows). D) Axial T2w MR shows hyperintensity in the left precentral gyrus (solid arrow) s/o MCA territory infarct

Figure 4

Aspergillus skull base osteomyelitis (SBO) (sino-orbital and sino-cranial aspergillosis). A-C) 22-year-old female with sino-orbital aspergillosis. A) Axial unenhanced computed tomography (CT) shows opacification of the left ethmoid air cells (solid arrow) with a hyperdense mass lesion seen extending into the ipsilateral orbit (arrows) causing proptosis. B) Coronal reformatted image shows the orbital extension (*). There is opacification of the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses with dehiscence of the inferior wall of left orbit (solid arrow) and intra-orbital extension. Foci of calcification are also noted (arrows). C) Axial T2w MR shows a lobulated, T2 hypointense mass in the retrobulbar space of the left orbit (solid arrow). Mucosal thickening in the anterior ethmoid air cells (arrow). D) 21-year-old male with sino-cranial aspergillosis. Coronal T1 FS post gad image shows enhancement of the clivus (arrows) and the left muscles of mastication (*). There is extension of enhancing soft tissue into the left cavernous sinus (solid arrow). In addition, a bright enhancing dural based mass lesion is seen in relation to the inferior temporal lobe (arrowheads)

Patterns of bone destruction were also peculiar to each organism, although erosion and sequestra formation are seen in both bacterial and fungal SBO (Figures 2A and 5). Osteomyelitis in bacterial SBO represents progression from cellulitis to osteitis and finally osteomyelitis [25]. Thus, involvement of pneumatised trabecular bone is late and may show formation of abscess cavities [19]. Infection spreads to involve the periosteum, leading to periosteal elevation and reaction. Absence of periosteal elevation from the orbital wall has been described as a predictor for fungal aetiology in the past [26]. In addition, due to the invasive nature of the organisms in fungal SBO, there is a rapid spread of infection through the Haversian system of bone, which gives rise to a permeative pattern of bone destruction (Figure 5). Rarefaction was also seen. Thus, absence of periosteal elevation with presence of permeative destruction is a strong predictor for fungal aetiology.

Figure 5

65-year-old male with fungal skull base osteomyelitis (SBO). A) MIP axial bone window computed tomography shows permeative destruction involving the right zygoma and pterygoid bone (arrows). Sequestrum formation is seen along the anterior and laterall walls of maxillary sinus (solid arrow). B) In a cranial section, extensive permeative destruction seen involving the right lesser wing of sphenoid (arrows). There is associated mucosal thickening in the ethmoid air cells (*) and sphenoid sinus (arrowhead). Soft tissue is seen in the right orbit extending till the orbital apex (solid arrows)

The diagnosis of fungal SBO on MR was also facilitated by its characteristic signal on pulse sequences. There was a striking hypointensity on T2-weighted sequences (Figure 4C), with blooming often seen on the gradient echo sequences. This is due to the metabolism of organisms, which concentrates ferromagnetic elements (iron, manganese, zinc) within the fungal elements [27]. This is also the reason behind their hyperdense appearance on CT scans. Calcification was also noted in fungal sinusitis in a few studies [11,12] (Figure 4B), which has been postulated to be dystrophic calcification due to deposition of minerals over the necrotic tissue [28].

While both fungal species are angio-invasive, there is marked propensity of Mucor to cause invasive thrombosis of vessel walls [29] and hence produce both clinically as well as radiologically the ‘black turbinate’ comprising necrotic eschar tissue. The imaging correlate of this does not enhance on administration of intravenous iodinated or gadolinium contrast [30]. Other patterns of enhancement were also seen; notably, central or patchy irregular non-enhancement, presumably due to non-uniform distribution of necrotic lesions. On the other hand, Aspergillus commonly produces dural based intracranial masses, which are composed of fungal elements and are homogenous in appearance. The enhancement paralleled their composition and bright, uniform enhancement was seen [11] (Figure 4D).

There were certain limitations to our study. There were only a few studies that satisfied our inclusion criteria. Of these, there were only 2 studies that addressed head-to-head comparisons among any 2 of these entities; hence, we had to extrapolate the data obtained from studies detailing individual aetiologies to derive any possible differentiation between the entities. A meta-analysis could not be performed due to heterogeneity of data. There was often lack of complete information on one or the other parameters in most of the studies. In addition, the majority of the studies were at risk of bias due to their retrospective nature; hence, more prospective studies investigating our review question should be performed in future.

Conclusions

The chief differentiating features between bacterial and fungal SBO are in terms of presentation and radiological involvement. Bacterial SBO is mostly of otogenic origin with involvement of CNs VII-XII; while in fungal SBO origin is rhinogenic, with higher incidence of orbital, vascular and intracranial extension, palsy of CN III-VI, and permeative bone destruction. Hypointensity on T2-weighed MR sequences and hyperdensity on unenhanced CT also favours fungal involvement. Mucorales SBO, in comparison with Aspergillus SBO, shows faster disease progression, black eschar, cerebral infarcts, and heterogenous post-contrast enhancement. On the other hand, Aspergillus SBO shows intracranial homogenous enhancing masses and greater incidence of concurrent pulmonary involvement. These are detailed in Tables 4 and 5. Systematic analysis of imaging features, aided by relevant clinical information, may thus allow us to make a reasonably accurate diagnosis for prompt targeted therapy as well as accurate prognostication of patients.

Table 4

Differentiation between bacterial and fungal aetiology SBO

Table 5

Differentiation between Aspergillus and Mucor SBO