Introduction

In this paper we refer to the phenotypes and stages described by Olivotto et al. [1], adapted by Soler et al. [2] and Muresan et al. [3].

Diagnosis and prevalence

The guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have been issued by European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in 2014 [4] and by American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) in 2011 [5]. There are certain differences in disease definition in the above-mentioned documents.

On the one hand, according to ESC, in an adult, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is defined by a wall thickness ≥ 15 mm in one or more left ventricular (LV) myocardial segments – as measured by any imaging technique (echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging [CMR] or computed tomography [CT]) – that is not explained solely by loading conditions. The clinical diagnosis of HCM in first-degree relatives of patients with unequivocal disease (left ventricular hypertrophy [LVH] ≥ 15 mm) is based on the presence of otherwise unexplained increased LV wall thickness ≥ 13 mm [4]. This definition aligns with everyday clinical practice. In this concept, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is an ‘umbrella’ term that encompasses a diverse and complex spectrum of genetic and acquired diseases [4].

On the other hand, ACCF/AHA defines HCM as unexplained LV hypertrophy associated with nondilated ventricular chambers in the absence of another cardiac or systemic disease that itself would be capable of producing the magnitude of hypertrophy evident in a given patient [5]. This definition is not compatible with advanced-stage disease and multi-system disorders.

In up to 60% of adolescents and adults with HCM, the disease is an autosomal dominant trait caused by mutations in cardiac sarcomere protein genes. Mutations in the genes encoding beta-myosin heavy chain (MYH7) and myosin-binding protein C (MYBPC3) account for most cases [4,6]. The most common mode of inheritance is autosomal dominant [4,6].

HCM is the most common heritable cardiomyopathy [6], traditionally believed to affect ~1 in 500 people. Recent investigations suggest even greater prevalence – a total of 1.4% participants had unexplained left ventricular hypertrophy in a population-based CMR study [7]. Lately, the prevalence of HCM has been estimated at 0.16% to 0.29% (≈ 1 : 625 – 1 : 344 individuals) in the general adult population [8]. It is likely that HCM affects approximately 20 million people globally [9]. That means most persons do not receive a diagnosis during their lifetime [9]. The underrecognition of HCM has disproportionately affected women [9]. However, there is no clear connection between the specific mutation and the HCM phenotype [8], and there is no specific role of genotyping in risk stratification [9]. Crucial management decisions in patients with HCM are based on clinical and imaging criteria [9].

Expression of the HCM phenotype is variable; penetrance is incomplete and age-dependent [7]. Hypertrophy becomes visible in approximately half of genotype-positive patients by the third decade of life, and approximately three-fourths become phenotype-positive by the sixth decade [8].

Another interesting feature of sarcomere protein mutations is pleiotropy. Mutations in the same gene could manifest as HCM, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), restrictive cardiomyopathy, and left ventricular non-compaction (LVNC) cardiomyopathy [1,8].

Genetic testing can also help to identify metabolic and storage phenocopies [8,9], present in about 10-15% of the patients [4].

Recent advances in noninvasive imaging – mostly scintigraphy utilizing bone tracers, T1-mapping CMR, and genetic testing have permitted a much better recognition of cardiac amyloidosis [10-12]. Some of the patients were initially misdiagnosed as HCM [11,12]. Among patients referred with initial diagnosis of HCM, the most common phenocopy is cardiac amyloidosis (9% prevalence); Anderson-Fabry (AF) disease was diagnosed only in 2% [11,12]. Differential diagnosis is of particular importance in early recognition, following the development of specific disease-modifying treatments: tafamidis in transthyretin-mediated cardiac amyloidosis, enzyme therapy for AF disease [11,13] (Figure 1).

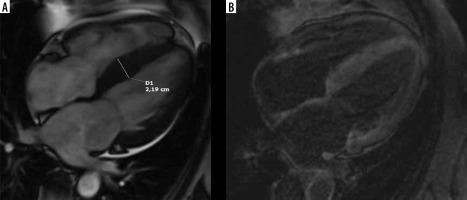

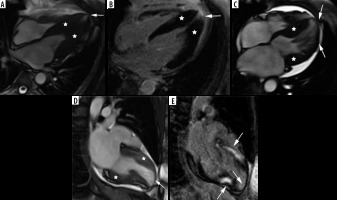

Figure 1

A 67-year-old woman with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy diagnosed by echocardiography presented with congestive heart failure, EF – 30%. Her coronary angiogram was normal. Cardiac magnetic resonance 4-chamber view: A) cine image demonstrating interventricular septum thickening, B) LGE image with suppressed blood pool and transmural enhancement of myocardium typical for amyloidosis; endomyocardial biopsy revealed SSA, genetic testing confirmed hereditary TTR amyloid; recurrent hospitalisations due to advanced heart failure during follow-up

The role of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

CMR is now considered an indispensable, complementary tool in the diagnosis and prognostication of HCM [3,7,14,15]. Most patients are initially imaged by echocardiography [3-5], but not all myocardial segments may be adequately visualized [3,7,15,16]. Clinically relevant discrepancies in LV maximal thickness measurements are common between the 2 techniques, and CMR is much more accurate [7,14-16]; we observed this also in our group of patients. The fact is of clinical importance because maximal LV wall thickness is not only the diagnostic criterion, but it is also an important risk factor [4,17]. Moreover, only basal septal and posterior wall thickness are measured routinely and documented in a standard echocardiography record. CMR can identify hypertrophy of anterior, lateral wall, and apex undetected by echocardiography, because it covers the entire ventricle with high resolution and contrast with excellent endocardial visibility [7,15-17]. Practical importance is illustrated in [18], where CMR recognized 20 more cases of HCM missed by echocardiography in a population of 155 athletes with abnormal ECG.

CMR enables quantitative assessment of LV mass, hypertrophy of the RV wall, elongated mitral valve leaflets contributing to LVOTO, and late onset of hypertrophy in adults [14,16,17]. It is postulated that the diagnostic criteria for HCM in CMR may require refinement because of differences in normal wall thickness by segment, sex, and body size [7]. In [19] normal values of left ventricular myocardial thickness for every segment are given. A unique feature of CMR is tissue characterization. LGE provides accurate, non-invasive assessment of regional myocardial fibrosis with histological validation, while diffuse interstitial myocardial fibrosis is quantified by post-contrast T1 mapping – ECV [2,13,20-22]. The examples of LGE patterns in HCM patients are shown in Figure 2.

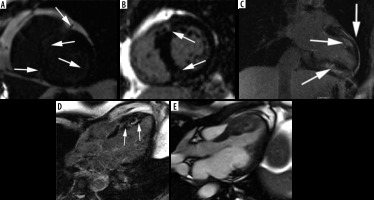

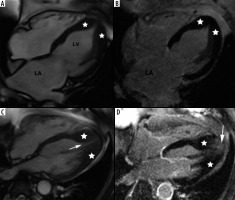

Figure 2

Most common LGE distribution patterns in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A) Extensive midwall LGE in short-axis view (arrows). B, C) Patchy enhancement at insertion points of the RV wall into the anterior and posterior interventricular septum (arrows): B) short-axis view, C) modified 2-chamber view, D) patchy mid-wall delayed enhancement in the hypertrophied segments (arrows), E) cine image corresponding with D

Chan et al. [23] showed that %LGE ≥ 15% of total LV mass was associated with a 2-fold increase in SCD at 5 years compared to patients with no LGE. Conversely, the absence of LGE was associated with lower risk of SCD [23]. The findings were confirmed by meta-analysis in 2016 [24] and could not be incorporated in previously published guidelines [4,5]. Extensive LGE was also predictive of adverse LV remodelling and progression to systolic dysfunction (end-stage HCM) [23]. In a recent study of 2094 patients with HCM (17 years of experience) a novel risk factor for SCD was proposed to enhance the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Strategy for Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death in High-Risk Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy – “late gadolinium enhancement – identified fibrosis with diffuse and extensive distribution, either quantified (usually comprising about 15% or more of LV mass) or estimated by visual inspection to be extensive and diffuse, either alone or associated with other markers” [25]. Other novel risk factors proposed in [25] are end-stage disease and LV apical aneurysm with associated contiguous regional scarring.

Global ECV was superior to all tested clinical and CMR parameters including LGE and native T1 mapping to identify HCM patients with increased risk for SCD in the recent study of 73 HCM patients [26].

Strain analysis is a new promising tool; however, the type of algorithm employed during strain assessment has a significant impact on the results [27].

Our illustrative material consists of 91 studies of 88 patients referred for CMR at the Department of Diagnostic Imaging of the University of Opole Hospital from 2011 to 2019. The images were retrospectively analysed with dedicated software: syngo.via MR Cardiac Analysis (Siemens Healthineers), including LGE quantification, volume/time curve parameters, and LA volumetry.

We quantitated LGE in all our patients as LGE volume and % LGE mass. An alternative method of simplified, quick estimation of LGE in HCM suggested by Kłopotowski et al. in [28] was also used. Unfortunately, we do not have the possibility of myocardial mapping in our CMR laboratory yet; we would not be able to apply this measurement retrospectively anyway.

Additionally, the volume/time curve parameters were derived from cine images used for functional parameter estimation, as suggested in [29,30]. The software provided in syngo.via MR Cardiac Analysis calculates PER, PET, PFR, and PFT. The practical application of such data is difficult [31] because of inconsistent values of normal ranges provided by different authors [19,29,32], probably due to software differences.

The other parameters we assessed were left atrium volumetric, including LAEDV, LAVI, and LAEF acquired by biplane area method, as in [33-35]. In LAEF (< 38%), LAEDV (> 118 ml) and age (≥ 40 years) identified HCM patients at risk for development of AF [34].

Stage I: Non-hypertrophic HCM

Due to genetic testing, a new HCM subgroup has been identified: HCM – causing mutation carriers without LV hypertrophy, known as “genotype-positive-phenotype-negative” [36]. With CMR imaging; however, it is possible to discover a certain degree of cardiac hypertrophy [1], and other abnormalities like myocardial crypts, elongated mitral valve leaflets, accessory papillary muscles, and fibrosis [2,3,22] – see Figure 3. ECG abnormalities may be evident [1].

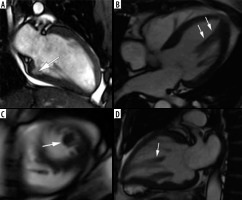

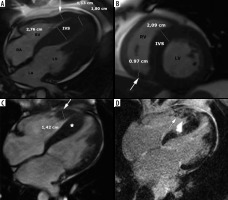

Figure 3

SSFP cine images – examples of findings characteristic for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) – causing mutation carriers. A) Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) image at end – diastole, 2-chamber view, showing myocardial crypt perpendicular to the endocardial border at inferior wall (arrow). B, C, D) 40-year-old woman with a family history of HCM presented with chest pain, dyspnoea, reduced exercise tolerance, palpitations, and anaemia. CMR SSFP cine images revealed abnormal papillary muscle (arrows) and a mild hypertrophy; B) 4-chamber view, C) short-axis view, D) 2-chamber view

We had no patients in this group, because no program of systematic genetic screening was conducted. One of our patients, however, a 40-year-old woman with a family history of HCM presented with chest pain, dyspnoea, reduced exercise tolerance, palpitations, and anaemia. CMR revealed an abnormal papillary muscle and borderline hypertrophy of 13 mm (Figure 3).

In [37] it was postulated that the identification of elongated mitral leaflets by CMR can represent a clinical marker in HCM family members without hypertrophy, whose genotype is unknown. In [35] Fahrad et al. demonstrated that LA dysfunction measured as decreased LAEF is detectable by CMR in preclinical HCM mutation carriers.

Stage II: The “classic” HCM phenotype

This stage is defined as hypertrophied and hyperdynamic LV with EF > 65% [1].

In our group 62 patients (70%) presented with this phenotype, similar to [1]. One patient died during follow-up due to unknown causes – she had numerous comorbidities.

The distribution of myocardial hypertrophy in classic HCM phenotype is variable [2,3,38,39], CMR is helpful in proper grouping according to phenotype [2,21]. LV wall thickness was greater in segments with late gadolinium enhancement than in those without [38].

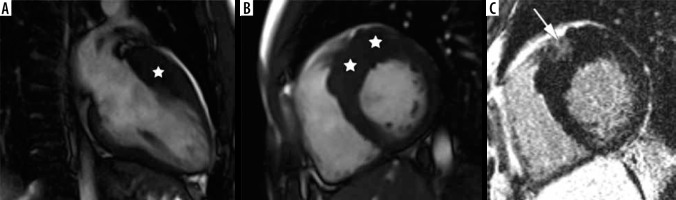

The most common form is sigmoid septum contour, affecting the confluence of the basal anteroseptal and anterior segments [2,21,38] – see Figure 4. This pattern of hypertrophy may be associated with LVOT obstruction and SAM [21]. In our group 46 patients presented with asymmetric septal hypertrophy – sigmoid septum contour (74% of classic phenotype).

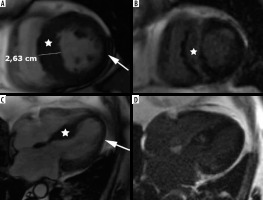

Figure 4

Distribution of hypertrophy – basal anteroseptal. A 29-year-old woman who presented with palpitations. A) Two-chamber SSFP cine cardiac magnetic resonance imaging image at end-diastole shows anterior hypertrophy (asterisk). B) Short-axis cine view demonstrates marked anteroseptal hypertrophy (asterisks). C) Corresponding LGE image showing the area of delayed enhancement (arrow)

The second most frequent form is the hypertrophy of medial inferior ventricular septum [21], creating reversed septal contour, sometimes associated with midventricular obstruction and apical aneurysm – see Figure 5. Localized apical aneurysms often develop later in life, implying a degree of remodelling. They are often unrecognized in echocardiography and are now recognized as a novel risk factor for sudden death [16,25,40]. Ventricular arrhythmia may occur, and catheter ablation of monomorphic VT can be effective [6,41]. Because thrombi may form in the aneurysm and cause systemic embolism, anticoagulation can be considered in these patients [40]. In some series LV apical aneurysms are associated with a 10% annual event rate [40], but the ESC guidelines do not recommend ICD placement based only on this risk factor [4].

Figure 5

Distribution of hypertrophy – reversed curvature with apical aneurysm. A 53-year-old man referred for cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) with a suspicion of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), EF – 75%. A) Systolic 4-chamber SSFP cine image demonstrates a “dumbbell” configuration of the LV cavity, mid-cavity constriction by hypertrophied segments (asterisks) and a thin-walled apical aneurysm (arrow), not visible in echo. B) LGE image in diastole showing hypertrophy (asterisks) and a subtle delayed enhancement thinned apical aneurysm (arrow). A 57-year-old woman with recurrent syncope and nSVT, suspected hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: C) systolic cine 4-chamber view, demonstrating hypertrophy (asterisks), thin-walled apical aneurysm (arrow), and relatively thin lateral wall (arrow), D) systolic cine 2-chamber view, demonstrating hypertrophy (asterisks) and thin-walled apical aneurysm (arrow), E) LGE 2-chamber view showing mid-wall, patchy delayed enhancement of the hypertrophied segments (thick arrows) and no enhancement of the aneurysm (thin arrow); EF was in the adverse remodelling range – 58%. The aneurysm was not visible in the echo examination. The patient refused ICD and was hospitalised because of arrhythmia and heart failure during the follow-up

In our group only 6 patients presented with midventricular hypertrophy in classic phenotype (9.6%). Three (3.4% of all HCM patients) developed small (< 2 cm) apical aneurysm without thrombi, 1 in classic phenotype, and 2 in stage III adverse remodelling. None of them was discovered by echocardiography. Contrary to [40], only 1 of our patients exhibited LGE in the aneurysm.

An important variant of hypertrophy is apical distribution, usually present in 5-25% of patients [2] – see Figure 6. In our series apical hypertrophy was present in 10 people – 16% of classic phenotype.

Figure 6

Distribution of hypertrophy – apical involvement, 4-chamber views. A, B) A 61-year-old woman previously diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) presented with palpitations – paroxysmal AF and nsVT, EF – 64%; cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) revealed mild hypertrophy of the apex (asterisks), please note large left atrium and B) no LGE; the patient received ICD and underwent two cryoablations because of recurrent AF and was hospitalised because of heart failure due to arrhythmia during the follow-up. C, D) A 58-year-old man referred for CMR because of suspected HCM in echo, apical hypertrophy more pronounced than in A, B. C) Cine image demonstrate spade-like appearance of LV (triangle). D) LGE image showing enhancement in hypertrophied apical segments; uneventful follow-up

Spade-like configuration of the LV cavity and giant inverted anterolateral T waves on the electrocardiogram are usually present [2,3,21,22]. Cardiac MRI is strongly recommended to diagnose and evaluate apical HCM because echocardiography has significant limitations in this region, in particular in correct differentiation of apical hypertrophy from LV noncompaction [21,22].

In a certain subgroup of patients hypertrophy also involves the RV wall – see Figure 7.

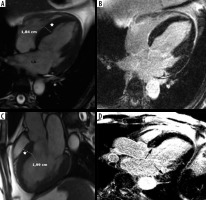

Figure 7

Distribution of hypertrophy with RV involvement. A, B) A 39-year-old gentleman with massive biventricular hypertrophy shown in SSFP cine images, arrow indicates free right ventricular wall, EF – 73%. C, D) A 36-year-old gentleman, referred for routine cardiac magnetic resonance imaging after alcohol septal ablation, EF – 59%. C) SSFP cine end-diastolic four-chamber image demonstrates IVS (asterisk) and free RV wall (arrow) hypertrophy. D) 4-chamber LGE image demonstrates patchy areas of delayed enhancement present also in hypertrophied RV wall (arrow) and probably post-ablation septal scar

We did not observe concentric, symmetric hypertrophy in classic phenotype – as in [2], contrary to [3,22].

Recently the RESTYLE – HCM trial has shown a significant antiarrhythmic effect of the late sodium current inhibitor ranolazine on ventricular ectopic burden in non-obstructive HCM. The drug can also be used to control anginal symptoms; however, the trial does not support the use to improve functional capacity and diastolic dysfunction.

Left ventricular tract obstruction

Patients with left ventricular tract obstruction (LVOTO) constitute an important subgroup of the classic HCM phenotype – hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM).

According to the literature, up to 70% of patients with classic HCM may have resting or provocable LVOTO [2,37]. Exercise (stress) echocardiography is currently considered the method of choice to provoke LVOT gradients, when absent at rest [9]. The resting gradient can also be quantified by phase contrast CMR sequences, although it increases the scanning time and may underestimate the values [2,3,21]. Gradient > 30 mmHg is considered significant, and in the presence of severe, drug-refractory symptoms > 50 mmHg may be considered an indication for invasive septal reduction therapies (SRT) including surgical myectomy (SM) or alcohol septal ablation (ASA) [41]. New pharmacological approaches – e.g. a novel myosin inhibitor (mavacamten) – may change therapeutic options in HOCM patients [41].

Cine MRI in a long-axis view can provide an accurate picture of the precise mechanism of outflow tract obstruction [2], see Figure 8. Turbulent flow is visibly generated by SAM and movement of subvalvular apparatus toward the basal interventricular septum, producing a posteriorly directed mitral regurgitant jet [2]. Elongated mitral leaflets associated with small LVOT represent an important contribution to LVOTO, and the ratio of AML/LVOT with a cut-off value of 2 was evaluated in [37], also in the context of most appropriate septal reduction strategy. Surgical myectomy can be combined with mitral valve correction, whereas ASA cannot.

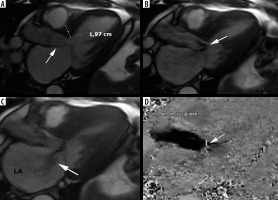

Figure 8

Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction: a 56-year-old gentleman diagnosed with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy referred for routine cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. A) Three-chamber diastolic cine image show anteroseptal hypertrophy and elongated anterior mitral leaflet (arrow), B) mid-systolic image show SAM and turbulent-velocity jet (arrow) within the LVOT, C) late-systolic image demonstrates posterior jet of dynamic mitral regurgitation caused by SAM; note enlarged left atrium, D) in-plane phase velocity image showing LVOTO high-velocity jet (arrow). Maximal LVOT velocity was 5.5 m/s, mitral regurgitation volume – 52 ml

Another interesting CMR parameter – the LVOT/Ao diameter ratio differed significantly among the 3 subgroups: non-obstructive 0.60 ± 0.13, latent 0.41 ± 0.16, obstructive 0.24 ± 0.09 [42]. In our cohort, LVOTO visible in the cine long-axis view was present in 20 patients – 32% of classic phenotype. The calculated pressure gradient range was between 9 and 148.8 mmHg. Most of these patients exhibited LVOT/Ao ratio < 0.5, in all of them the ratio was < 0.54 and AML/LVOT > 2 with one outsider whose echocardiography demonstrated LVOTO. In all patients without visible obstruction LVOT/Ao ≥ 0.58. AML and PML were elongated compared to the normal values listed in [37].

Pressure gradient correlated well with LVOT/Ao and AML/LVOT ratios. Higher PET and PER and high EF probably reflect the hyperdynamic state.

Two of our patients underwent SRT in the past: 1 ASA and 1 septal myectomy simultaneously with CABG.

Stage III: Adverse remodelling

Adverse remodelling is defined by progressive decreases in systolic function (EF 50-65%) superimposed to the classic HCM phenotype [1,2]. This stage is characterized by concomitant reduction or loss of LVOTO, progressive LV wall thinning, increasing LV fibrosis with relatively preserved clinical and haemodynamic balance [1-3] – see Figure 9. This seems to represent a selective pathway followed by about 15 to 20% of HCM patients, with the minority progressing to overt dysfunction [1]. Both LV and LA remodelling are common, and AF frequently leads to clinical progression. The long-term outcome of this group is not known, but cardiac mortality is estimated to be 3-5% per year [1]. It is striking that although this EF would be considered within normal range for other populations, in [43] it was shown that HCM patients in this group have a nearly 3-fold increased risk of developing overt left ventricular dysfunction. It was postulated that they would probably benefit from closer management [43].

Figure 9

Adverse remodelling. A 71-year-old man admitted after cardiac arrest caused by VT/VF, with persistent AF. He was diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) 1 year earlier, with an EF 55-60%, SAM, LVOTO, normal coronary arteries. Cardiac magnetic resonance images: A) short-axis SSFP cine view showing septal hypertrophy (asterisk) and lateral wall thinning (arrow), B) same level LGE image demonstrates large midwall area of delayed enhancement in hypertrophied septum (asterisk), C) SSFP cine 4-chamber view showing septal hypertrophy (asterisk) and lateral wall thinning (arrow), D) corresponding LGE image. During CMR study no LVOTO was demonstrated, EF equalled 51%, LAVI – 75 ml/m2, LAEF – 1%, LGE 12%. The patient received ICD as primary prevention, during the follow up successful shocks were delivered, due to recurrent electric storms with congestive heart failure he required frequent hospitalizations

The question arises: what is the trigger for adverse LV remodelling and dysfunction? Olivotto in [1] speculates that it is internal, noting severe HCM progression in patients with complex genotypes – double or triple sarcomeric mutations. External factors such as viral myocarditis or epicardial coronary disease in his opinion are only anecdotally associated. On the other hand, Frustaci et al. in their intriguing paper [44] detected histological signs of overlapping active myocarditis and a viral genome in 28 of 42 LV endomyocardial biopsy tissue samples from HCM patients with acute clinical deterioration. A viral genome was present in 14 of 28 patients with overlapping myocarditis. The authors concluded that myocarditis, often viral, represents a common cause of acute clinical deterioration in HCM. Recently Maron et al. in [39] introduced the concept of acquired HCM risk factors, postulating that nongenetic, potentially modifiable mechanisms may be involved in cardiomyopathic disease, even when there is also a genetic variant that indicates risk, similar to dilated cardiomyopathy in which the phenotype can also be triggered by various nongenetic factors such as alcohol, viral infection, and toxins [39]. Disease progression was attributed to multiple causes, including microvascular dysfunction, progressive myocardial fibrosis, and cardiomyocyte energy depletion in [41]. Disease progression may be subtle for a treating clinician due to preserved EF; in [41] the mean age at progression to heart failure is estimated to be after 65 years of age.

In our group 15 patients belonged to this stage, 17% of the whole cohort. Atrial fibrillation was documented in 5 (30%). Two patients had the ICD implanted and 1 successful shock was delivered. Two of the patients were not diagnosed as HCM by echo – their maximal wall thickness measured was below 15 mm.

Stage IV: Overt dysfunction

The high-risk phenotype of HCM with LV systolic dysfunction (LVSD), defined by an EF < 50%, previously called “end-stage disease (ES)” or “burnt-out” develops in a minority of HCM patients, roughly 3.5-10% in described cohorts [1,2,45,46].

It is important to realize that in HCM patients EF decreases from typical supranormal values, and EF slightly below the lower limits of normal subjects is substantially reduced for this population. Literally, this group encompasses both HFrEF and HFmrEF ranges, but due to unique characteristics of HCM this classification is not adequate. LVOT gradients are absent in this stage [1].

Olivotto in [1] characterized this advanced stage of the disease as spanning between the 2 extreme morpho-functional manifestations. The first was defined as the hypokinetic-dilated form (also called D-ES = ventricular dilatation end stage by Cheng in [45]) and is characterized by progressive LV wall thinning, LV dilatation, and spherical remodelling – see Figure 10. This variant may be hard to distinguish from a primary dilated cardiomyopathy, although residual hypertrophy is often retained [1].

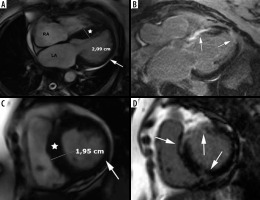

Figure 10

Overt dysfunction with hypokinetic-dilated form, D-ES. A 56-year-old man presented with decompensated CHF, low EF – 32%, recent infection, suspected myocarditis. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging revealed EF 24%, LVEDV – 263 ml, LVESV – 200 ml, LAEF – 38%, LAVI – 54 ml/m2, LGE 2%. A, C) SSFP end-diastolic cine images demonstrated IVS hypertrophy inconsistent with dilated cardiomyopathy and LA enlargement. B, D) Corresponding LGE images, small, patchy areas of delayed enhancement – arrows. The patient received ICD, during follow-up 2 successful shocks were delivered, he required frequent hospitalizations due to recurrent heart failure

The other variant, hypokinetic-restrictive (also called N-ES = normal ventricular size end stage), is characterized by a small and stiff LV with extreme, progressive diastolic dysfunction, marked biatrial dilatation, and AF, whereas systolic LV function is only mildly or moderately impaired – see Figure 11. These patients may present with clinical signs of low cardiac output due to restrictive filling rather than congestion [1]. Furthermore, most are not candidates for left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) because of their relatively small cavities and residual contractile function. Interestingly, the concept of possible myocardial recovery after LV unloading was presented in [1] and deserves further investigation in HCM LVSD patients.

Figure 11

Overt disfunction hypokinetic-restrictive, N-ES. A 61-year-old woman with persistent AF, nsVT, with a history of ICD explantation because of infective endocarditis presented with palpitations and dyspnoea. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) revealed LAEF – 39%, LAVI – 64 ml/m2, LVEDV – 159 ml, LVESV – 87 ml, EF – 45%, LGE 17%. A) SSFP cine 4-chamber view showing septal hypertrophy (asterisk) and lateral wall thinning (arrow), note biatrial enlargement. B) corresponding LGE image showing extensive, almost transmural delayed enhancement areas (arrows). C) Cine short-axis view showing again septal hypertrophy (asterisk) and lateral wall thinning (arrow). D) Corresponding LGE image showing extensive delayed enhancement areas (arrows). Her HCM risk score was 5%, she refused another ICD implantation and required recurrent hospitalizations because of heart failure during the follow-up

In 2006 Harris et al. [46] described CMR in 6 HCM LVSD patients, and each showed large areas of LGE indicative of fibrosis, frequently transmural. Further studies revealed that the CMR features of HCM LVSD also span between the 2 extreme forms, with dominating LV or LA remodelling. LGE is more extensive in D-ES and LAVI is larger in N-ES. Both LGE and LAVI were significant predictors of poor outcomes in [45], in which CMR scans of 63 patients with ES were analysed.

Accelerated clinical deterioration was reported to occur usually over 5-6 years [1,2].

An interesting paper on HCM with LV systolic dysfunction [43] has recently been issued, combining the data from 11 high-volume HCM centres making up the international SHaRe Registry (Sarcomeric Human Cardiomyopathy Registry). Nearly 7000 HCM patients were observed from 1960 through March 2019, including 553 patients with HCM-LVSD. In this population LVSD affected around 8% of patients with HCM. Seventy-five per cent of them experienced adverse events, including 35% experiencing a death equivalent to an estimated median time of 8.4 years after developing systolic dysfunction. Risk factors of poor prognosis for HCM LVSD patients were multiple pathogenic/probably pathogenic sarcomeric variants, atrial fibrillation, and left ventricular ejection fraction < 35%. Genetic substrate appeared to play a role in both prognosis (multiple sarcomeric variants) and the risk for incident development of HCM-LVSD (thin filament variants). The fate of an individual patient is difficult to predict; many patients do not experience the composite outcome [43]. The patients with LVOTO were less likely to develop systolic dysfunction. LGE was more prevalent in the patients with HCM-LVSD [43].

As far as treatment is concerned, the current guidelines systematically recommend standard HF therapy: the routine measures include ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta blockers specific for heart failure, spironolactone, and loop diuretics. Oral anticoagulants are important in cases of AF or apical aneurysm. No significant improvement occurred in the recent randomized trial with trimetazidine [41,47]. Data on sacubitril-valsartan are awaited in HCM [41]. Moreover, overt LV dysfunction should be considered as a potential indication for ICD (or CRT-D) placement [25], even if this factor is not included in the ESC risk score. It is important, however, to take into account that age older than 60 years is itself associated with low likelihood of SCD [25]. Tailored surgical options may be considered: mitral plasty, LVAD, and cardiac transplantation [1,41]. In a recent study of 118 LVSD HCM patients [48] the contemporary natural history of ES, utilizing advanced heart failure treatment strategies, was analysed. Annual mortality was 2%, and survival at 10 years was 87% (95% CI: 67, 95). However, aborted adverse HCM events (including appropriate ICD shocks, heart transplant, and resuscitated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest) were 8% per year, 4 times the HCM mortality. HCM-related deaths were 50% lower than previously reported in ES-HCM. This highlights the potential role of appropriate intervention strategies.

Our population of patients differed substantially from previously described [1], because we did not observe a large cohort of patients for a sufficiently long period of time. In [43] systolic dysfunction developed a median of 15 years after initial diagnosis of HCM. The patients who develop LV dysfunction during follow-up are classified as incident HCM-LVSD and are lacking in our cohort. Our end-stage group consists mostly of patients referred to CMR because of heart failure symptoms and reduced EF by echo, some with initial diagnosis of myocarditis, so they are classified as prevalent HCM-LVSD [43]. Patients were designated as having HCM-LVSD in our study when CMR revealed both LVMT ≥ 15 mm and LVEF < 50%. Interestingly, echocardiography revealed left ventricular maximal thickness > 15 mm only in 3 of them. Surprisingly, our end-stage group was dominated by men – 10 out of 11 were male (90%). It consisted of 12.5% of the whole cohort – significantly more than in [1]. No LVOTO was present. We observed 2 deaths – 1 because of progressive heart failure in a patient with ICD, and 1 extra cardiac – ruptured aortic aneurysm. Adequate ICD intervention was delivered twice in 1 patient. Three patients needed unscheduled hospitalizations. Nine suffered from concomitant hypertension. All patients presented with either LAEF < 38% or LAEDV ≥ 118 ml – risk of AF by [34], only 1 had small atria. Only 4 of our patients had LVEDVI ≤ 90 ml/m2, belonging to N-ES [45]. Most of the patients in this group were described as dilated cardiomyopathy by treating physicians.

Conclusions

HCM is an extremely heterogeneous disease [1]. The patients suffering from it constantly defy rigid classifications. The reasons for such diversity even within members of the same family are poorly understood. Epigenetic and environmental factors are postulated [1,39].

There is limited awareness among patients and physicians regarding the risk of disease progression in HCM [1], and its recognition is therefore delayed, often to the advanced and truly “end-stage” phases. The HCM group with overt left ventricular dysfunction is underrecognized, often labelled as dilated cardiomyopathy. This poses significant difficulties in assessing risk ratios and optimal therapy choices. There is a clear need to better understand HCM-LVSD to improve risk stratification and to inform clinical management.

The role of CMR is crucial, particularly in precise diagnosis, novel risk factors, and the LV dysfunction group [15,25,45].

Historically, HCM was considered a rare disease with an ominous prognosis. Now, it is recognized worldwide as a relatively common genetic heart disease. Important diagnostic and management strategies effectively influence the natural history of HCM [48,49].

These include CMR, stress echocardiography, refined algorithms for risk stratification, ICD, septal reduction therapies, anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and LV aneurysms, and heart transplantation [9].

In specialized referral centres in the USA a recent analysis revealed that most deaths in affected patients are unrelated to HCM, with noncardiac coexisting cardiac conditions and cancer greatly influencing survival, particularly in older patients [9,48,49].