Introduction

Acute pulmonal embolism (PE) is a very common diagnosis in acute care and can cause diverse symptoms, ranging from mild respiratory distress to sudden death. In acute care units the annual incidence rate is from 0.2 to 0.8 /1000 [1,2]. Today, pulmonary angio-computed tomography (CT) after contrast administration is the gold standard method. The aim of the diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism is to have the dose of the contrast agent adapted to the body weight, with the associated improved resolution of the smaller lung vessels [3].

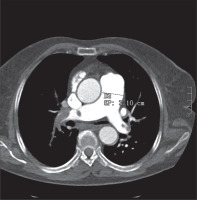

In this retrospective single centre study, we tried to ascertain if there is a correlation between D-dimer levels in positive acute thromboembolic thoracic CT and the axial diameter of the pulmonary trunk (Figure 1), and if there is a cut-off D-dimer level regarding the uni-or bilateralism of the lesions and with the presence of pulmonal trunk involvement.

Today’s clinicians use diagnostic scores to identify risk stratification like the classic Wells score (WS), modified WS, simplified WS, revised Geneva score (GS), simplified GS, and the YEARS score. In our Institution clinicians use clinical signs and measurement of the D-dimer level in peripheric blood to confirm the suspicion of acute PE. D-dimer is a fibrin cleavage product that results from cleavage of cross-linked fibrin by factor XIIIa. Its low-level plasma expression expresses the control of haemostasis by coagulation factors and fibrinolytic system. Increased D-dimer values serve as activation markers of haemostasis, a condition that is present in any thrombotic process. Normal values preclude significant activation. The exact quantification of D-dimer levels has an important role in guiding therapy [4]. But which levels of D-dimer are pathologic? The D-dimer level has a low specificity but a very high sensitivity. It can be elevated in many other pathologies, after surgery, but also after bone fractures or infections. Many previous studies have shown that the D-dimer test is highly sensitive (> 95%) in acute deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism [5]. In our hospital levels under 500 ng/ml fibrinogen equivalent units (FEU) are considered normal.

Another key in the pathophysiology of acute PE is the dilatation of the main pulmonal trunk (MPA). In a study from 2012 [6] the authors found no correlation in women between age and MPA in a healthy reference group. But which clinical significance has the dilatation of the MPA? There are many other causes of MPA dilatation, such as pulmonary arterial hypertension, Eisenmenger syndrome, high altitude, congenital cardiac shunting, pulmonal valvular stenosis, congenital, infectious, rheumatologic/vasculitis, connective tissue diseases, and idiopathic or traumatic causes. The most common cause is pulmonary hypertension (PH). Increased intrapulmonary pressures lead to vascular thickening and dilation with increased vascular wall shear stress, as well as increased collagen and elastin deposition in the adventitia layer of the pulmonal trunk. The continuous high pressure in the MPA causes cell activation and vascular remodelling in hypoxia-induced PH [7]. Another key in understanding pulmonal thromboembolism is to analyse the correlation between MPA-dilatation and the side involvement, i.e. if there is a predilection of involving the right or the left side in trunk dilation and non-trunk dilatation.

Material and methods

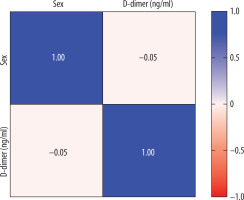

In this retrospective study, we considered 100 patients who underwent thoracic computed tomography angiography (CTA) with contrast administration at our Institution in the period January 2015 – January 2019 after admission to the Emergency Department. All patients presented clinical signs of PE and underwent D-dimer examination levels in acute care. The range of blood D-dimer levels were between 300 and 39.958 ng/ml (Figure 2). The diameter of the main pulmonary artery (MPA) ranged from 21 to 50 mm. We considered a normal reference of 29 mm in men and 27 mm in women [6]. Retrospectively we also analysed whether there were other associated reasons for high D-dimer levels.

All of the authors confirm that the research was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was not obtained.

Imaging protocol

Multiple detector computed tomography (MPCT) scans were performed in our department with two multislice CT-scanners. All the examinations were performed on a dual-source CT scanner (Somatom Definition Flash; Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany and Somatom Drive; Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany) with patients lying supine on the table with their arms at the side of their body, with spiral acquisition. Scanning parameters are given in Table 1. Thoracic CTAs were obtained after intravenous administration of 70 ml of 350 mg iodine/ml iodinated contrast material (Iobitridol, Xenetix 350, Guerbet, France) at a flow rate of 4 ml/s, followed by a 50-ml saline flush through an 18-gauge catheter placed in an antecubital vein using an automatic power injector (Medrad Stellant, Bayer); a bolus-tracking technique was adopted, with the region of interest (ROI) placed in the pulmonal trunk (threshold 100 Hounsfield units [HU]). We analysed only axial images with a slice thickness of 1 mm.

Table 1

Scanning and reconstruction parameters for pulmonal computed tomography angiography

Results

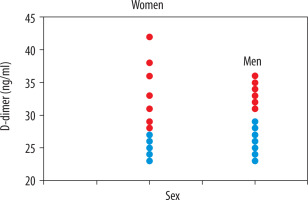

Considering the correlation between D-dimer levels and the axial diameter of the pulmonal trunk, we found a weak correlation, with a Pearson correlation r value of 0.2141 (Table 2). Using the Spearman correlation, we also found a weak value (p = 0.2871). The relationship between the D-dimer level and gender (Figure 3) gave a negative Pearson score of –0.05 (almost zero correlation).

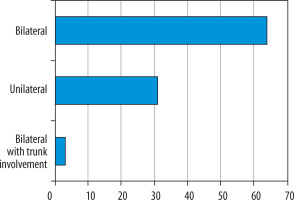

Considering the correlation between the axial diameter of the pulmonal trunk and gender-related distributions (Figure 4), we found that female patients had higher axial diameters (58.3% above 27 mm) in PE versus male patients (46% above 29 mm), which means that women have a higher risk of developing pulmonal hypertension in PE than men [8]. Hormonal influence must be considered in the pathophysiology of trunk dilatation. Considering the correlation between the location (uni- or bilateralism) and the D-dimer levels, we found a weak correlation with a Pearson value of 0.2572 and a Spearman value of 0.2789. 64% of the study population had bilateral pulmonal involvement, 31% had unilateral involvement, and only 3% had a bilateral PE with trunk involvement (Figure 5). In the search for associated diseases or conditions that could lead to an increase in D-dimer levels, we found neoplastic diseases in 11 patients (11%) (four patients with a non-surgically treated lung tumour in chemotherapy and one in immunotherapy, one patient with a cerebral neoplasm in follow-up after surgical therapy and chemotherapy, and five patients with a recent diagnosis of an adenocarcinoma of the colon). In 35 patients (35%) we found a coexisting chronic atrial fibrillation. Twenty-six patients (26%) showed renal pathologies like mild chronic renal failure. In nine patients (9%) there was a chronic congestive cardiac failure. Associated deep vein thrombosis was found in 46 patients (46%). This indicates the presence of coexisting and overlapping conditions in these patients, which also increase D-dimer levels (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3

The study parameters

Table 4

Minimum values, 25% percentile, median, 75% percentile and maximum values

| Factor | Trunk diameter(mm) | D-dimer(ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 100 | 100 |

| Minimum value | 23 | 300 |

| 25th percentile | 24 | 1904.75 |

| Median | 26 | 4061 |

| 75th percentile | 29 | 6483.25 |

| Maximum value | 42 | 39,958 |

Conclusions

The clinical presentation of acute PE is varied. The most frequent clinical symptoms are chest pain, tachycardia, hypotension, dyspnoea, cough, and haemoptysis [9]. But what can a radiologist expect from the CT examination? Can there be any correlation between clinical and radiological parameters? In this retrospective study we tried to find correlations between different radiological and clinical parameters in the imaging “outcome’, i.e whether parameters like D-dimer, diameter of MPA, uni- or bilateralism of PE, and gender-related factors are radiologically significant. Considering that not every centre has a dual-source CT, we analysed parameters that are simple in their clinical and radiological evaluation. Assuming D-dimer levels under 500 ng/ml to be negative, we found one of 100 patients (1%) with a D-dimer-level of 300 ng/ml with PE.

A study from 2014 [10] proposed an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off, but the results were not satisfactory. In other studies several scores for quantification of the clot were proposed, such as the CT severity score and CT obstruction index developed by Mastora et al. and Qanadli et al., respectively, but these are not routinely used in clinical practice [11,12].

The different correlation types show low correlation statistical data. The “strongest” weak correlation was between D-dimer levels and the axial diameter of the pulmonal trunk. Considering the correlation between the axial diameter of the pulmonal trunk and gender-related distributions, we found that female patients had higher axial diameters than men. We confirmed that women have a higher risk of developing pulmonal hypertension in PE than men [8].

Another weak relationship (almost zero) was found between D-dimer level and gender. Regarding the correlation between uni- or bilateralism of thromboembolism and the D-dimer levels, we found a weak correlation. The limitations of this retrospective study are, in our opinion, the use of only one clinical parameter like the D-dimer level to assess acute PE. We did not include diagnostic scores to identify risk stratification, such as the classic Wells score (WS), modified WS, simplified WS, revised Geneva score (GS), simplified GS, and the YEARS score.

Other drawbacks of this study are the exclusion of the age of the patients and the fact that a dilatation of MPA can have other causes, like cardiac shunts, arterial hypertension, Eisenmenger syndrome, high altitude, pulmonal valvular stenosis, infections, and connective tissue diseases, as well as idiopathic or traumatic causes. Another limitation is the absence of a control group and the presence of coexisting pathologies that increase D-dimer levels.

This retrospective study showed that D-dimer levels, the diameter of the pulmonal trunk, its location, and gender-related distributions have almost no correlation and are not significantly predictive in imaging.