Introduction

Congenital anomalies of seminal vesicle are rare but well recognised in the literature. It is important to be familiar with the imaging findings of seminal vesicle anomalies so as not to misinterpret them with other conditions. Congenital anomalies of seminal vesicles are classified in three categories: number (agenesis, duplication, fusion), canalisation (cysts), and maturation (hypoplasia) [1]. Although usually diagnosed incidentally, they can be associated with infertility, haematuria, hydronephrosis, and perineal pain [2].

Anatomy

The seminal vesicles (SVs) are paired tubular accessory glandular structures of the male reproductive system. They are located in the retro-peritoneum, posterior to the prostate and between the bladder and rectum. SVs and the vas deferens join to form the ejaculatory duct, which opens into the prostatic urethra on each side. SVs secrete seminal fluid, which provides nutrition for the spermatozoa, promotes motility of sperms, and increases the stability of sperm chromatin. It constitutes the majority of the ejaculate. The size of the SVs increases with age until adulthood and starts to decrease in the elderly. The normal range of SV width and length are 0.4 to 1.4 cm and 1.9 to 4.1 cm, respectively [3]. Mild asymmetry is common.

Embryology

The ureteral bud arises from the distal mesonephric duct during the fifth week of gestation and extends in a dorsocranial manner to meet metanephric blastema and induce differentiation to form the definitive kidney. Appendix of the epididymis, paradidymis, epididymis, vas deferens, ejaculatory duct, seminal vesicle, and hemitrigone are formed by differentiation of the mesonephric duct. Both ureteral bud and mesonephric duct are needed for the development of the normal kidney. SV develops as dilatation of the distal mesonephric duct at the 12th week. Later the mesonephric duct forms the vas deferens. Developmental defects of the mesonephric duct before the seventh week result in both renal and reproductive ductal anomalies, while kidneys develop normally if the defect occurs after the seventh week [4].

In the case of complete failure of the mesonephric duct, ipsilateral kidney, hemitrigone, and seminal vesicle will not develop [5]. Seminal vesicle will develop normally while ipsilateral kidney is agenetic or dysplastic if the ureteral bud fails to meet the metanephric blastema [6]. Maldevelopment of the distal mesonephric duct causes absence of the ureteral bud; thus, this results in ejaculatory duct obstruction with seminal vesicle cyst and ipsilateral renal agenesis or dysplasia [7]. If the ureteral bud meets with the mesonephric duct in a more cranial position, absorption of caudal mesonephric duct will be delayed, and this results in the distal ureteral bud emptying into mesonephric duct derivatives such as the vas deferens, seminal vesicle, or ejaculatory duct [8]. There is no known common embryological process between the seminal vesicle and contralateral kidney [9].

Agenesis

Seminal vesicle agenesis is a rare anomaly with a reported incidence of 0.08% in a robotic laparoscopic radical prostatectomy series [10]. It can be unilateral or bilateral. Bilateral SV agenesis is mostly seen as a primarily genital form of cystic fibrosis. It is associated with mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene, and agenesis may be seen as a consequence of luminal obstruction with thick secretions [11]. These patients usually have bilateral vas deferens agenesis but normal urinary tract.

Unilateral seminal vesicle agenesis is seen if embryologic insult occurs before the seventh week; thus, it is usually associated with other anomalies, most commonly ipsilateral renal agenesis. But fewer than 10% of the cases can have normal kidneys [12].

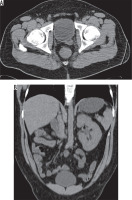

Although patients are generally asymptomatic, it may result in infertility [13]. It can be diagnosed with all imaging modalities. It is characterised by non-visualisation of seminal vesicles posterior to the prostate (Figure 1). It is essential to check for any abnormality in kidneys when seminal vesicle agenesis is encountered (Figure 2). It may also be associated with other genitourinary anomalies such as ectopic ureter opening (Figure 3).

Figure 1

32-year-old male with nephrolithiasis. Axial computed tomography image of the abdomen shows no seminal vesicle posterior to the prostate on the left

Fusion and duplication

There are few reported cases of seminal vesicle fusion in the literature [4,14]. Diagnoses were based on surgical exploration or vasography, but in one report in which they retrospectively evaluated the preoperative sonographic images, they realised that the seminal vesicles were fused in the midline by an isthmus [4]. This anomaly causes modification of the surgical technique if radical prostatectomy was planned; thus, it is important to diagnose preoperatively.

Seminal vesicle duplication is another very rare anomaly with only two reported cases, and none of them described imaging features of this anomaly [15,16].

Hypoplasia

Hypoplasia refers to congenital underdevelopment of the seminal vesicles. Hypoplasia was defined as a maximum diameter smaller than 50% of normal or < 5 mm [17]. This condition usually is associated with other genitourinary anomalies such as absence of the vas deferens [1]. It is mostly seen in patients with azoospermia. It can be diagnosed with transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS), but computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide more repeatable measurements and delineated images (Figure 4).

Cyst

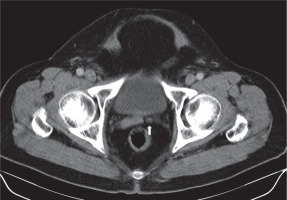

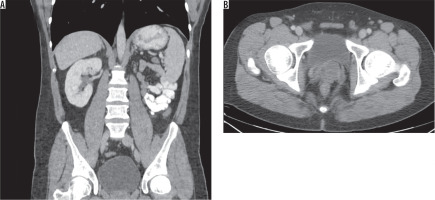

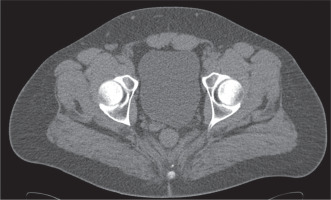

The seminal vesicle cyst is a rare entity, which can be acquired or congenital. The incidence of seminal vesicle cyst is 0.005%, and it is associated with an ipsilateral renal anomaly in two-thirds of cases [18]. A study revealed up to 0.46% incidence of seminal vesicle cyst in patients with ipsilateral renal agenesis [19]. It is rarely associated with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease [20]. Seminal vesicle cysts can be accompanied with other congenital genitourinary abnormalities (Figure 5). Zinner syndrome is a rare condition, which is characterised by a triad of unilateral renal agenesis or dysplasia, ipsilateral seminal vesicle cyst, and ejaculatory duct obstruction. It is related to the common embryologic origin of the mesonephric duct and ureteral bud, which are associated with the development of genital and urinary tracts. A few variants of this syndrome were reported including renal agenesis with contralateral seminal vesicle cyst, renal agenesis with contralateral seminal vesicle hypoplasia, renal agenesis with ipsilateral seminal vesicle cyst and contralateral seminal vesicle hypoplasia (Figure 6), and renal agenesis with bilateral seminal vesicle cyst [9,18,21-26]. Dysplastic kidney with bilateral seminal vesicle abnormality or dysplastic kidney with ectopic ureter draining into ipsilateral seminal vesicle cyst can be seen (Figures 7 and 8).

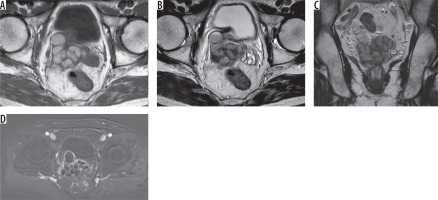

Figure 5

62-year-old male with elevated prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels. A) Axial T1 and (B) T2 images show cystic dilatation of the left seminal vesicle. C) Coronal T2 images show ectopic opening of the dilated ureter into the seminal vesicle cyst. D) Axial subtracted magnetic resonance image shows no enhancement of the cyst except the walls

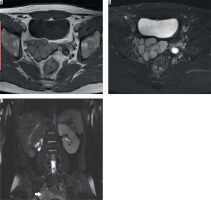

Figure 6

26-year-old male with intermittent perineal pain. A) Axial T1 and (B) fat-sat T2 images show hyperintense multi-lobulated right seminal vesicle cyst and left seminal vesicle agenesis. C) Coronal fat-sat T2 image shows right kidney agenesis and hypertrophied left kidney. Right seminal vesicle cyst can also be seen (arrow)

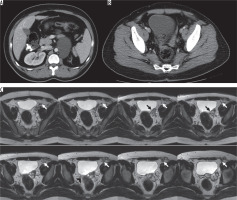

Figure 7

31-year-old male patient with left orchiectomy secondary to testicular tumour. A) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of abdomen shows left dysplastic kidney and left paraaortic metastatic lymphadenopathy. B) No seminal vesicle is seen on the right. A soft tissue density extending to the left side of bladder, is continuous with left seminal vesicle. C) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen: No seminal vesicle is seen on the right (arrowhead). Dilated cystic structure (black arrow) is continuous with the stump of the left vas deferens (white arrow)

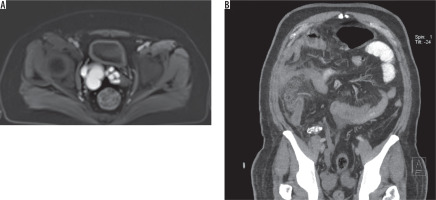

Figure 8

51-year-old male with perforated cholecystitis. A) Axial contrast enhanced fat-sat T1 image shows right seminal vesicle cyst. B) Oblique coronal computed tomography image reveals calcified dysplastic right kidney with dilated ureter, which drains into the right seminal vesicle cyst, and increased density in mesenteric fat due to cholecystitis (not shown)

Seminal vesicles enlarge with the accumulation of secretions due to atresia of the ejaculatory duct after puberty, and this leads to the formation of a cyst. The clinical presentation is related to the size and location of the cyst. Seminal vesicle cysts less than 5 cm are usually asymptomatic. When symptomatic it can cause dysuria, frequency, recurrent infections, painful ejaculation, perineal pain, or infertility [27]. Giant cysts (larger than 12 cm) can even cause bladder or colonic obstruction [28].

Differential diagnosis of seminal vesicle cysts includes prostatic, utricular or Müllerian cysts, abscesses, ureteroceles, benign or malignant tumours of the bladder, rectum, sacrum, or lymph nodes [27]. Accompanying renal abnormalities are diagnostic clues of Zinner syndrome. Also, seminal vesicle cysts are paramedian to the bladder while Müllerian duct cysts or ejaculatory duct cysts have midline and ectopic ureteroceles have a more lateral location.

Different imaging studies may be helpful in diagnostic work-up. Abdominal or transrectal ultrasonography may reveal an anechoic mass in the seminal vesicle region while showing agenetic or dysplastic kidney. CT also offers a noninvasive diagnosis of pelvic cysts. Seminal vesicle cysts can be seen as a low attenuated retrovesicular mass superior to the prostate gland or cystic pelvic mass with thick irregular walls on CT. But MRI is the ideal imaging study to assess seminal vesicles due to high resolution, superior soft tissue contrast, multiplanar imaging capabilities, and no use of ionising radiation. Seminal vesicle cysts appear hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Cysts can contain debris seen as increased intensity on T1-weighted images secondary to previous bleeding or infection. No contrast enhancement is seen except the walls of the cyst. Subtraction images can be used to control enhancement in cases of T1 hyperintense cyst content (Figure 5). MRI can also aid surgical planning with excellent delineation of anatomic structures. No FDG uptake is seen inside the cyst in positron emission tomography (PET) images. Vasography and percutaneous fine-needle aspiration are no longer used unless for therapeutic intentions. Only a seminal vesicle cyst will contain spermatozoa, which differentiates it from other cystic pathologies.

Treatment options are aspiration or surgical excision, which depends on the size and location of the cyst and whether it is symptomatic or not. Patients without any symptoms should not be treated, and surgical excision should be preferred in symptomatic cases because aspiration is associated with high risk of recurrence (Figure 9) [27]. Imaging follow-up is preferred in asymptomatic cases.

Conclusions

Seminal vesicles are a part of the male genitourinary system and are critical for male fertility. Congenital anomalies of SV often seen with other defects in the genitourinary system due to their common embryological origin. Although they rarely cause symptoms, surgical correction may be needed. SV anomalies can be accurately diagnosed with all imaging modalities, but MRI is superior to other modalities, with excellent soft tissue resolution, and it plays a critical role in surgical planning.