Introduction

Posterior fossa abnormalities are among the most common referral indications for foetal magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI). The spectrum of posterior fossa abnormalities is found in about 1 in 5000 live births [1]. Ultrasonography is the initial imaging modality for assessment of the foetal posterior fossa. Abnormal findings on ultrasonography such as abnormal cerebellar biometry, posterior fossa cyst, or abnormal cerebellar morphology warrant further evaluation with FMRI. FMRI offers excellent soft-tissue contrast resolution, multiplanar capabilities, and is a versatile tool for diagnosis of foetal posterior fossa abnormalities [2]. The neurological prognosis of different posterior fossa anomalies varies widely, and FMRI plays a crucial role in counselling patients and families regarding continuation of pregnancy and possible post-natal developmental outcome. Multiple previous studies have shown that FMRI is highly accurate in detecting most foetal central nervous system anomalies with sensitivity and specificity ranging from 85% to almost 100% when performed after 20 weeks of gestational age [3-5]. However, the accuracy of FMRI is lower if performed in early gestation [6].

The cerebellum is one of the first central nervous structures to form and one of the last to mature. This wide period of development makes it susceptible to many possible insults resulting in a broad spectrum of possible abnormalities. The development of the cerebellum is intimately linked to brainstem development with both of these structures deriving from the mesencephalic-metencephalic complex [7]. Moreover, posterior fossa abnormalities are sometimes associated with other cranial and extracranial anomalies such as congenital heart disease, and renal, limb, and facial anomalies [8]. Normal development of the posterior fossa is represented in Figure 1.

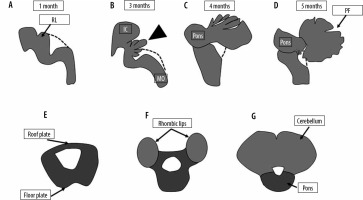

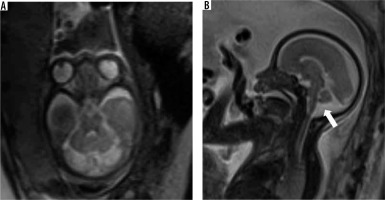

Figure 1

Normal development of the posterior fossa. The pons and cerebellum develop from the metencephalon, which in turn derives from the anterior part of the rhombencephalon. The roof plate of the neural tube at the level of the metencephalon develops 2 swellings called the rhombic lips, which enlarge to form the cerebellum. The floor plate forms the pons. The dotted line represents the roof of the fourth ventricle, which is not demonstrable on foetal MRI. The roof of the fourth ventricle is gradually closed by the developing vermis (arrowhead). Closure of the 4th ventricle roof is usually complete by around 18 weeks. IC – inferior colliculus, MO – medulla oblongata, PF – primary fissure, RL – rhombic lips

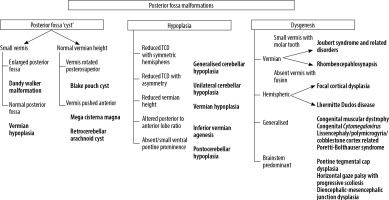

The spectrum of posterior fossa abnormalities is wide, and various classification systems have been proposed [1,9,10]. Posterior fossa abnormalities can be broadly divided into malformations and disruptions. Malformations are morphological defects resulting from intrinsically abnormal developmental processes, while disruptions are defects occurring due to extrinsic breakdown or interference with an originally normal developmental process [11]. Examples of malformations are Joubert syndrome and rhombencephalosynapsis, while disruptions include cerebellar agenesis and global or unilateral cerebellar hypoplasia. However, there is considerable overlap between these categories. A recent study by Aldinger et al. [12] has shown that the majority of cases diagnosed as ‘Dandy Walker malformation’ are due to disruptive mechanisms rather than being true malformations. A practical classification system based on morphology was provided by Patel et al. [9] in 2002 and later updated to include genetic information [10]. An algorithmic approach to diagnosis of foetal posterior fossa anomalies is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Algorithmic approach to diagnosis of posterior fossa anomalies on foetal MRI. TCD – trans-cerebellar diameter

FMRI scans are routinely performed at a field strength of 1.5 T. Image interpretation is mainly done on T2-weighted images. These are acquired using ultrafast imaging sequences such as half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin echo (HASTE), T2 turbo-spin echo (TSE), or steady-state free precession (SSFP). Acquiring images in true axial, coronal, and sagittal planes is important to assess the central nervous system. T1-weighted images using fast spoiled gradient echo sequence can be obtained to look for haemorrhage and fat. Optional sequences include diffusion-weighted imaging and diffusion tensor imaging [13].

Developmental imaging anatomy of the posterior fossa

The posterior fossa is located between the tentorium cerebelli superiorly and the foramen magnum inferiorly. It consists of the brainstem, midline cerebellar vermis, 2 cerebellar hemispheres on each side of the vermis, the 4th ventricle, and the cisterna magna. Foetal MRI is generally performed after 18-20 weeks of gestation. By this gestational period the 4th ventricle is visible on the midline sagittal image as a triangular shaped structure and is completely covered by the cerebellar vermis. The tentorium is oriented perpendicularly to the occipital bone and its insertion is located at the torcular Herophili. The primary fissure of the vermis, which separates the smaller anterior lobe from the larger posterior lobe, can be visualised by around 22 weeks [14]. The posterior lobe to anterior lobe ratio is ~2 : 1. The other fissures of the cerebellar vermis are appreciated much later in the gestational period [15]. The prepyramidal and secondary fissure can be seen after 32 weeks of gestation. Hemispheric fissures, being shallow, are difficult to appreciate on foetal MRI. Transcerebellar diameter (TCD) and vermian height (VH) are important biometric markers for the assessment of cerebellar development and should be compared with nomograms in all cases [16]. A normal imaging appearance of the posterior fossa at different gestational ages is shown in Figure 3. A checklist of features to be assessed when reading a FMRI done for assessment of the foetal posterior fossa is presented in Table 1. In this pictorial review we present the imaging features of foetal posterior fossa anomalies as seen on FMRI.

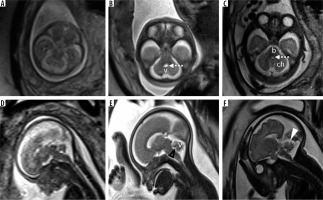

Figure 3

Normal appearance of the posterior fossa at 18, 24, and 30 weeks of gestation in axial (top row) and mid-sagittal plane (bottom row). Note the progressive development of the cerebellar vermis on the mid-sagittal images. Also note the fastigial point (black arrowhead) and primary fissure of the vermis (white arrowhead). The posterior lobe is the part of the vermis posteroinferior to the primary fissure, while the anterior lobe lies anterosuperior to the primary fissure. Note that the posterior lobe:anterior lobe ratio is ~2 : 1. v – cerebellar vermis, ch – cerebellar hemisphere, b – brainstem. Dotted arrows – 4th ventricle

Table 1

Checklist of imaging features to be assessed in suspected posterior fossa malformations

Posterior fossa anomalies

‘Cystic’ lesions of the foetal posterior fossa

Dandy-Walker malformation (DWM)

Classic DWM consists of a triad of an enlarged posterior fossa with lambdoid-torcular inversion, cystic dilatation of the 4th ventricle, and small, superiorly rotated vermis (tegmento-vermian angle > 45 degrees)/absent vermis [17]; (Figure 4) all 3 features must be present to categorise the anomaly as DWM. Terms such as Dandy-Walker variant or continuum have been used to describe the condition where only 1 or 2 of the criteria have been met. These terms, however, represent a broad spectrum of anomalies and do not provide an accurate representation of the anomaly in a particular patient. Hence a more accurate anatomic description of the anomaly such as vermian hypoplasia, Blake pouch cyst, or global cerebellar hypoplasia is preferred over use of the term Dandy-Walker variant [1]. Ventriculomegaly is often present in DWM. Supratentorial anomalies such as corpus callosal dysgenesis, heterotopias, and occipital encephalocele are commonly seen in association with DWM. Additional benefits of MRI over ultrasound in DWM are the ability to accurately assess the degree of vermian development and to document the presence of supratentorial anomalies.

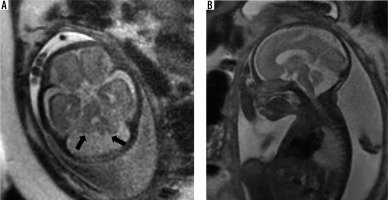

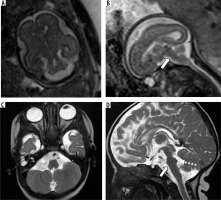

Figure 4

Dandy-Walker malformation – gestation age 21 weeks. Axial (A and B) and sagittal (C) T2w HASTE images show enlarged posterior fossa with a large 4th ventricle and high tentorium. Vermis is very small in size (black arrow). Also note the associated meningocele in the occipital bone (white arrow)

Blake pouch cyst (BPC)

It presents as a retro/infracerebellar cystic lesion, which typically ‘lifts’ the vermis posterosuperiorly. (Figure 5) BPC occurs due to lack of fenestration of 1) the membrane separating the foetal 4th ventricle from the cisterna magna and 2) the foramen of Luschka, resulting in a CSF-filled diverticulum of the 4th ventricle enlarging caudally to the cerebellar vermis [17]. The tegmento-vermian angle is usually less than 30 degrees and the vermis is normal in size. The posterior fossa is not enlarged. There are usually no supratentorial anomalies except for ventriculomegaly. Post-natal outcomes can range from spontaneous resolution of the cyst to persistent mass effect and hydrocephalus requiring decompression [18,19]. The presence of a normal sized vermis with a well-defined fastigial point, normal size of posterior fossa, and lack of other associated anomalies help to differentiate it from the more sinister DWM [20].

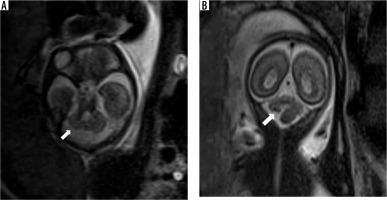

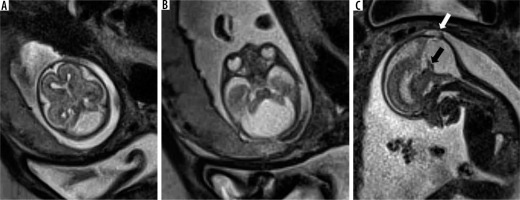

Figure 5

Blake pouch cyst – gestation age 22 weeks. Axial and sagittal (A and B) T2w HASTE images show a normal sized vermis rotated posterosuperiorly with tegmento-vermian angle of 20 degrees (dotted lines). Note the cystic space communicating with the 4th ventricle inferior to the cerebellar vermis (arrows). Post-natal MRI (C and D) shows normal size and morphology of the vermis with mildly increased tegmento-vermian angle. Post-natal neurological assessment was within normal limits

Arachnoid cyst

Arachnoid cyst is an encapsulated collection of cerebrospinal fluid trapped between duplicated layers of the arachnoid membrane. It can be retrocerebellar, supravermian, lateral to cerebellar hemispheres, or anterior to brainstem. It is characterised by a mass effect on adjacent structures in the form of displacement and flattening. (Figure 6). The 4th ventricle can be flattened or effaced. Scalloping of the occipital bone can occasionally be seen. It is usually an isolated finding with no other co-existing anomalies.

Mega cisterna magna (MCM)

It is defined as a retrocerebellar CSF space greater than 10 mm in anteroposterior diameter. The 4th ventricle, vermis and cerebellar hemispheres are normal. (Figure 7) It can be considered as a normal variant and has a good neurodevelopmental outcome [21]. The tegmento-vermian angle is normal, and the 4th ventricle is not dilated. Although MCM tends to have a lesser mass effect, differentiation from a retrocerebellar arachnoid cyst can often be difficult.

Figure 7

Mega cisterna magna – gestation age 24 weeks. Axial and sagittal (A and B) T2w HASTE images show large retrocerebellar cystic space with normal tegmento-vermian angle. Note the lack of flattening of the posterior cerebellar surface (cf. arachnoid cyst)

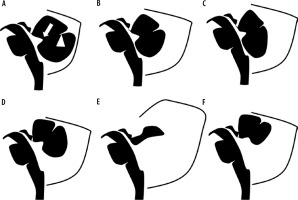

A schematic representation of the spectrum of cystic malformations of the posterior fossa is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8

Diagrammatic representation of ‘cystic’ malformations of the posterior fossa: A) normal foetal posterior fossa, B) mega cisterna magna, C) arachnoid cyst, D) Blake pouch cyst, E) Dandy-Walker malformation – note the enlarged posterior fossa with high riding tentorium, F) vermian hypoplasia. Fastigial point – arrow, primary fissure of the vermis – arrowhead

Hypoplasia/agenesis

Global cerebellar hypoplasia

This can result from both malformations and disruptions. The transverse cerebellar diameter is smaller than expected for gestational age with both the cerebellar hemispheres and vermis being small with prominent subarachnoid spaces. It has been reported in association with several chromosomal and genetic syndromes.

Unilateral cerebellar hypoplasia

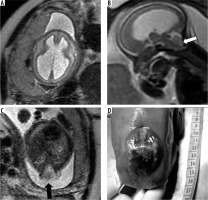

This is usually secondary to disruptions such as cerebellar haemorrhage. There is asymmetry in the cerebellar hemispheres with one hemisphere being smaller than the other. (Figure 9) Gradient echo images can be useful to look for evidence of haemorrhage in such cases.

Vermian hypoplasia

Controversy exists with respect to the terminology used to describe this condition, characterised by a small vermis that incompletely covers the 4th ventricle. It has also been referred to as Dandy-Walker variant or Dandy-Walker continuum by some authors [15,22,23]. The vermian height is smaller than expected for gestational age. The part of the vermis below the fastigial point may be deficient or small. The brainstem vermian angle is usually between 30 and 45 degrees.

Vermian agenesis

This can be an isolated anomaly or can be associated with other brain anomalies like Joubert syndrome. It is diagnosed by an abnormal cleft separating the cerebellar hemispheres on axial images with no vermis being visible. It is distinguished from DWM by the absence of a posterior fossa cyst and a normal sized posterior fossa. A dysplastic rudiment of the anterior lobe may be present in some cases. Sagittal images can be misleading due to partial volume effects from the cerebellar hemispheres. Hence axial and coronal images should be used to make this diagnosis. (Figure 10) Post-natal neurological outcome is poor.

Pontocerebellar hypoplasia (PCH)

This is a group of rare autosomal recessive genetic disorders that are characterised by a small cerebellum and small to absent ventral pontine prominence. (Figure 11) The neurodevelopmental outcome is usually poor. This imaging morphology is not specific for this group of disorders and can also be seen in other conditions – for example, in congenital disorders of glycosylation.

Dysgenetic malformations

Joubert syndrome/molar tooth sign-related disorders

This group of disorders, of which Joubert syndrome is a classical example, is characterised by dysmorphology of the midbrain which on axial sections resembles a molar tooth. This is due to abnormally deep interpeduncular fossa, thickened, parallel, and horizontally oriented superior cerebellar peduncles, and vermian hypoplasia. (Figure 12) Supratentorial anomalies such as callosal dysgenesis, ventriculomegaly, and neuronal migration disorders can be associated [24]. Post-natal outcome is generally poor with the majority having severe disability [25].

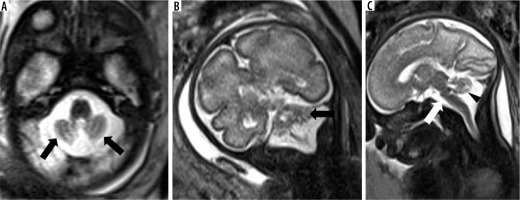

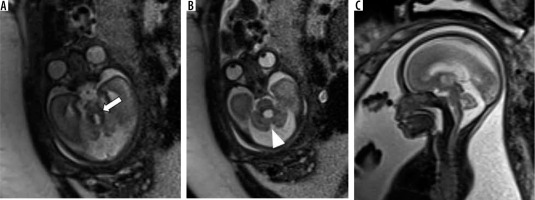

Figure 12

Joubert syndrome – gestation age 24 weeks. Axial (A) T2w HASTE image at level of the midbrain shows horizontal and parallel orientation of the superior cerebellar peduncles giving ‘molar tooth appearance’ (arrow). Axial image at level of the pons (B) and mid-sagittal image (C) shows hypoplastic vermis (arrowheads)

Rhombencephalosynapsis (RES)

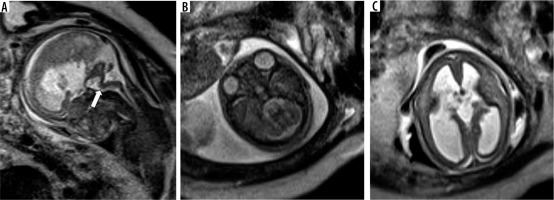

This is a rare malformation characterised by the absence of the cerebellar vermis with the cerebellar hemispheres fused across the midline. (Figure 13) The cerebellum appears horseshoe shaped. Sagittal images can show an apparently ‘large vermis’ due to the cerebellar hemispheres occupying the midline, and hence can be misleading. Axial and coronal images clearly show the absence of vermis and horizontal orientation of the cerebellar folia, which are continuous across the midline. It is usually associated with supratentorial anomalies such as corpus callosal agenesis and ventriculomegaly and facial anomalies. Postnatal outcome is variable depending on the severity of the anomaly and the presence of associated brainstem and supratentorial anomalies [26].

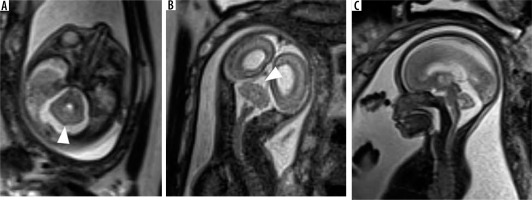

Figure 13

Rhombencephalosynapsis – gestation age 22 weeks. Axial (A) and coronal (B) T2w HASTE images show fusion of the cerebellar hemispheres across the midline (arrowheads) with no visible vermis. Midline sagittal (C) T2w HASTE image shows partial volume from the cerebellar hemisphere, which can mimic the vermis

Cerebellar cortical dysplasia

Dysplasia involving the hemispheric cortex of the cerebellum can be focal or diffuse. MR imaging findings that can be identified are the absence of horizontal foliation, large vertical or disorganised fissures, irregularity of the cerebellar hemispheric surface, heterotopias, hemispheric hypertrophy, and cyst-like cortical hyperintensities. These findings are, however, difficult to demonstrate on foetal MRI before the 3rd trimester [27]. Diffuse dysplasia is associated with congenital muscular dystrophy syndromes, congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, and various genetic disorders [9]. Many of these disorders can also be associated with small cerebellar cysts [28].

Brainstem predominant malformations

This group consists of malformations such as pontine tegmental cap dysplasia (PTCD), horizontal gaze palsy with progressive scoliosis (HGPPS), and mesencephalic-diencephalic junction dysplasia. PTCD is characterised by flattened ventral pons and a characteristic cap-like protuberance on the dorsal surface of the pons (Figure 14). HGPPS is characterised by butterfly shaped medulla and dorsal pontine cleft. However, these imaging features may be difficult to identify in FMRI.

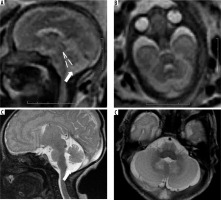

Figure 14

Pontine tegmental cap dysplasia – gestation age 22 weeks. Axial (A) and sagittal (B) T2w HASTE images show flattened ventral surface of the pons and a small bulge on the dorsal surface of the pons. These findings are more readily apparent in the post-natal MRI images (C and D). Note the cap-like bulge on the dorsal surface of the pons in image D (dotted arrow)

Miscellaneous anomalies

Chiari malformation type 2

It is seen in association with open spinal dysraphism. It is characterised by small posterior fossa, pear shaped cerebellum, descent of the brainstem and cerebellar vermis through the foramen magnum with tectal beaking. The 4th ventricle appears elongated and is low lying [15] (Figure 15).

Figure 15

Chiari 2 malformation – gestation age 20 weeks. A) Axial T2w image shows dilatation of bilateral lateral ventricles. B) Sagittal T2w image shows small posterior fossa with effaced 4th ventricle and crowded foramen magnum (white arrow). C) Axial T2w image through the lumbar spine showing a defect in posterior elements of vertebra with herniation of neural elements into amniotic sac through the defect (black arrow). Termination of pregnancy was done. D) Photograph of the abortus showing a large sac-like external protrusion in the lumbar region with no skin covering consistent with myelomeningocele

Occipital meningocele/encephalocele

This is caused by a mesodermal developmental anomaly resulting in a defect in the calvarium and dura associated with herniation of meninges, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and/or brain tissue through a defect that is usually covered by the scalp. A meningocele has only meninges and CSF as content (Figure 4C), while an encephalocele has brain tissue as herniating content. It usually occurs in the midline between the foramen magnum and lambda. Herniated contents can include the occipital lobe, cerebellum, or brainstem.

Kinked/z-shaped brainstem

This is a rare anomaly caused by arrested brainstem development at around 7 weeks of gestational age, with resultant abnormal persistence of brainstem flexures (Figure 16). It can be seen in congenital muscular dystrophies, tubulinopathies, and X-linked hydrocephalus. Unlike the brainstem-predominant malformations described earlier, kinked brainstem is almost always accompanied by other anomalies such as ventriculomegaly, cerebellar hypoplasia, neuronal migration disorders, or corpus callosal dysgenesis. Neurodevelopmental outcome is usually very poor [29,30].

Figure 16

Z-shaped brainstem – gestation age 21 weeks – sagittal (A) T2w HASTE image shows small vermis and abnormal Z-shaped morphology of the brainstem due to kinking (arrow). Axial (B) T2w HASTE image through the posterior fossa shows hypoplastic cerebellum. C) Axial T2w HASTE image through the lateral ventricles shows ventriculomegaly. Termination of pregnancy was done

Conclusions

Posterior fossa malformations have a broad spectrum of post-natal outcomes from incidental benign findings with normal developmental outcome to sinister pathologies in which termination of pregnancy can be considered. Foetal MRI is an invaluable tool in detecting, confirming, and prognosticating posterior fossa malformations.