Introduction

With the total number of diabetes patients expected to reach 439 million by 2030 [1], the prevalence of diabetic nephropathy (DN) is expected to increase because it affects approximately one-third of people with type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. Moreover, various factors are at play, which delay the diagnosis of diabetes so much that many diabetics present with complications like diabetic retino-pathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy [2].

DN is a common complication of diabetes due to histological changes induced by chronic hypoxia and haemodynamic abnormalities, which affects the filtration process. One of the earliest biomarkers of diabetic nephropathy is the excretion of albumin/protein in the urine. With the progression of diabetes mellitus and subsequent renal damage, there is an increase in excretion of albumin from intermittent to persistent and from mild to severe. Currently, detection of albumin or protein in the urine (microalbuminuria or proteinuria > 0.5 g/24 hours) is most commonly used to identify diabetic nephropathy [3]. But, by the time diabetic nephropathy is identified using albuminuria, renal structural changes are mostly intractable. Moreover, microalbuminuria in early-stage DN is usually intermittent, shows diurnal variation, and the results are prone to be influenced by a variety of factors, i.e. exercise, febrile illness, urinary tract infection, etc. Because DN is a strong predictor of adverse cardiovascular events [2] and is also the most common (44%) cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [4], early detection of renal damage becomes imperative to initiate an intervention to stall the process.

Therefore, there is a need for early detection of diabetic nephropathy using a reliable non-invasive method; magnetic resonance (MR) diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) can be helpful for this. DWI and DTI are recent techniques that allow for the assessment of the random movement of water molecules in renal parenchyma, thereby providing an indirect estimation of structural and functional information of the kidney without the use of intravenous contrast material [5-10].

Ischaemia is one of the major causes of cellular damage in diabetic nephropathy, and chronic hypoxia causes cellular oedema and atrophy [11]. The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), which is derived from DWI after taking into consideration both the effects of capillary perfusion and diffusion of water molecules within the renal parenchyma, allows early detection of ischaemic and hypoxic renal injury [12-14].

DTI is a non-invasive technique based on DWI, which analyses the directionality of water diffusivity. Because kidneys have well-defined structural organization consisting of glomeruli, tubules, and collecting ducts that cause preferential diffusivity of water molecules within the parenchyma, there is preferential transport of water molecules in collecting ducts, tubules, and vessels that are radially aligned towards the pelvis [14]. Any changes in renal parenchymal tissue organization or microstructural integrity due to diabetes would cause changes in directional diffusivity, which can be picked up by DTI [5,10]. Directional diffusivity or anisotropic properties of the tissues can be quantitatively represented by the fractional anisotropy (FA) using DTI.

Early diagnosis of DN is imperative because high doses of thiamine and its derivate benfotiamine have been shown to retard the development of microalbuminuria in experimental DN [15], and similarly sulodexide significantly reduced albuminuria in micro- or macro-albuminuric type 1 and 2 diabetic patients [16].

Hence, in this study, we intend to compare the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), FA, and ADC values between the control group and diabetics having normoalbuminuria/microalbuminuria/proteinuria to ascertain the usefulness of MR-DWI and DTI in diabetic nephropathy.

Material and methods

Subject selection and description

After obtaining written informed consent, study subjects (n = 100) who were referred to the Department of Radiodiagnosis for MRI Lumbosacral Spine between November 2019 and November 2020 were included in our cross-sectional analytical study. Diabetic study subjects were further sub-grouped into those with normoalbuminuria (NA) with urine albumin level < 30 mg/dl, microalbuminuria (MI) with urine albumin level of 30-300 mg/dl (early clinical nephropathy), and proteinuria (MA) with urinary protein excretion of > 300 mg/dl (signifying overt nephropathy).

Inclusion criteria

diabetic patients of both genders aged between 20 and 90 years: diabetes defined by the criteria – HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl [17];

healthy volunteers of both genders aged between 20 and 90 years with HbA1c 3.8-5.7%, random blood sugar 79-140 mg/dl, normal eGFR, i.e. > 90 ml/min/1.73 m2 in most healthy people or 60-89 ml/min/1.73 m2 in elderly people, with no other finding indicative of kidney diseases, such as oliguria and albumin/protein in urine, and no history of diagnosis/treatment for diabetes.

Exclusion criteria

small kidneys (craniocaudal dimension < 8 cm) [18] and loss of corticomedullary differentiation, abnormal renal anatomy, renal calculus, hydronephrosis, and renal trauma on screening ultrasound or MRI (balanced turbo field echo [BTFE] sequence);

general contraindications for MRI: metallic implants, cochlear implants, pacemakers, claustrophobia;

clinical history of urinary tract infection.

Procedure

A detailed profile of the patient including signs and symptoms, past and family history, treatment history, and biochemical investigations (serum creatinine, HbA1c, urine albumin/protein levels) were recorded. eGFR was calcu-lated from the National Kidney Foundation eGFR calculator, which is based on the CKD-EPI creatinine 2009 equation [19]. Written consent was obtained, and it was ensured there was no contraindication for MRI scanning. The patient was then placed in a supine position on the gantry table and an external surface coil was placed over the abdomen. Imaging was done on a Philips Achieva 1.5 Tesla MRI machine.

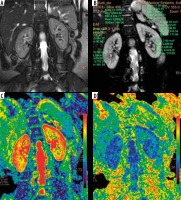

A 3-plane localizer was obtained for the planning of the various sequences. Then, a respiratory triggered BTFE sequence was obtained in the coronal plane of the abdomen with the following parameters: TR/TE = 3.4/1.68 ms, slice thickness = 6 mm, field of view (FOV)= 355 × 286 mm, and number of slices = 30. A renal anatomy survey was done on the BTFE sequence images to rule out the presence of any exclusion criteria. Next, the DTI sequence was obtained in the coronal plane of the abdomen using 6 directions and 2 b-values of b = 0 and 600 mm2/s with slice thickness = 6 mm. ADC and FA measurements were then recorded by drawing regions of interest (ROI) over the medulla and cortex on the ADC and FA maps at the upper, middle, and lower poles of both kidneys (Figure 1). An average of the 6 readings was recorded as the final ADC and FA values in a subject.

Figure 1

Representative images of the balanced turbo field echo (BTFE) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) sequences used in the study with the region of interest (ROI) placed in the cortex and medulla

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test and t-test (2 samples assuming equal variance) were used to evaluate the difference between the study groups, and the level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.001.

The Pearson correlation test was used to correlate eGFR and HbA1c values with mean ADC and FA values of the renal cortex and medulla.

Receiver operator curve (ROC), area under the curve, sensitivity, and specificity were calculated for the differentiation of normo-albuminuria (0-30 mg/dl) in the control and diabetic study groups.

Results

Of the 118 patients enroled in our study, 18 were excluded. Of the remaining 100 subjects, 57 were male and 43 female. The mean age of the patients was 53 years, with the most common age group being 60-70 years.

Fractional anisotropy values amongst different groups

Mean medullary FA values in the control group, NA, MI, and MA were 0.42 ± 0.0239, 0.38 ± 0.0275, 0.35 ± 0.0431, and 0.32 ± 0.0370, respectively (Table 1). Mean cortical FA values in the control group, NA, MI, and MA were 0.19 ± 0.0348, 0.25 ± 0.0492, 0.27 ± 0.0320, and 0.36 ± 0.0526, respectively (Table 1). Mean FA values of medulla were significantly higher than those of cortex in the control (0.42 vs. 0.19) as well as in the diabetics group (0.34 vs. 0.30) with p < 0.001 (Table 2).

Table 1

Trends of mean fractional anisotropy (FA) values of renal medulla and cortex

Table 2

Summary of the t-test results of all the parameters in the study subjects

Mean medullary FA values were significantly higher in the control group than among the diabetics (0.419 ± 0.024 vs. 0.346 ± 0.042), while significantly higher cortical FA values were noted in the latter (0.303 ± 0.067 vs. 0.194 ± 0.035) with p < 0.001 (Table 2).

There was an increasing trend in the FA values of the medulla while going from the control group to the MA group, while a reverse trend was seen for cortical FA values (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Increasing trend of mean fractional anisotropy (FA) values in the renal cortex and decreasing trend of FA values in the renal medulla in the various groups

Using one-way ANOVA, the differences in both the cortical and medullary FA values were found significantly different between controls and diabetic sub-groups, i.e. NA, MI, and DM with a p-value < 0.001. Additionally, utilizing the unpaired t-test it was found that the FA values were significantly different between FA values of healthy volunteers and each of the diabetic sub-groups and between the NA and MA sub-groups, with a p-value < 0.001. However, there was no significant difference between the NA and MI sub-groups in both the cortex and medulla, and between the MI and MA sub-groups in the medulla (Table 2).

Apparent diffusion coefficient values in different groups

Mean ADC values in the renal cortex in the control group, NA, MI, and MA were 3.307 ± 0.341, 2.724 ± 0.471, 2.534 ± 0.318, and 1.89 ± 0.31, respectively (Table 3). The mean cortical ADC was significantly lower among the diabetics than in the control subjects (2.309 ± 0.515 vs. 3.307 ± 0.341) (Table 2). The ADC values of the cortex showed a decreasing trend going from the control group to proteinuria subjects (Figure 3).

Table 3

Mean ADC values in renal cortex

| Groups | Mean ADC values (× 10-3 mm2/s) – cortex | Count |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 3.307 ± 0.341 | 27 |

| Normoalbuminuria | 2.724 ± 0.471 | 19 |

| Microalbuminuria | 2.534 ± 0.318 | 23 |

| Proteinuria | 1.89 ± 0.31 | 31 |

Figure 3

Trends of mean apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values in renal cortex in different groups (control group to diabetic patients with proteinuria)

One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences in cortical ADC values between controls and diabetic sub-groups, i.e. NA, MI, and DM with a p-value < 0.001. Using unpaired t-test cortical values were found to be significantly different between controls and each of the diabetic sub-groups, the NA and MA, and the MI and MA sub-groups with a p-value < 0.001. However, the difference was not significant between the NA and MI sub-groups (Table 2).

Mean fractional anisotropy and apparent diffusion coefficient values to estimated glomerular filtration rate

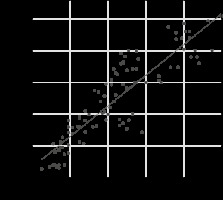

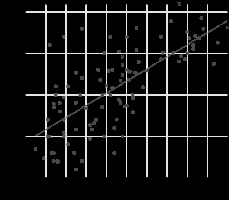

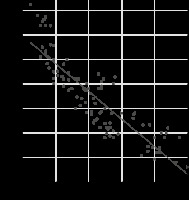

One-way ANOVA test showed a significant difference between average medullary FA, cortical FA values, and cortical ADC values of the patients with eGFR > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and normal healthy controls (Table 2). There was a strong positive correlation of renal cortex ADC (r = 0.88) values and renal medullary FA values (r = 0.88) with eGFR (Figures 4 and 5), whereas a strong negative correlation was noted in cortical FA values (r = –0.86) with eGFR (Figure 6).

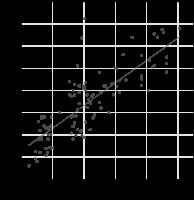

Figure 4

Scatter plot showing a positive correlation between cortical apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)

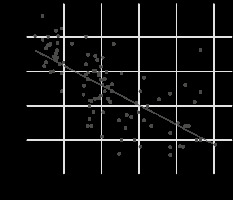

Figure 5

Scatter plot showing a positive correlation between medulla fractional anisotropy (FA) values and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)

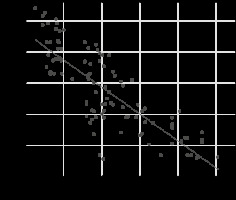

Figure 6

Scatter plot showing a negative correlation between cortex fractional anisotropy (FA) values and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)

Mean fractional anisotropy and apparent diffusion coefficient values to HbA1c

A strong positive correlation of renal cortical FA values (r = 0.88) with HbA1c concentration was noted (Figure 7), whereas a strong negative correlation was noted in cortical ADC values (r = –0.69) and medullary FA values (r = –0.86) with HbA1c (Figures 8 and 9).

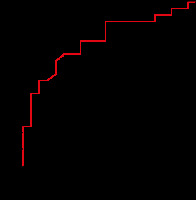

Receiver operator curve of fractional anisotropy values in the medulla to differentiate control from NA

The cut-off value was 0.4 with an area under the curve (AUC) = 0.76. With FA values of the medulla below 0.4, we could identify diabetics with normo-albuminuria with a sensitivity of 64% and specificity of 80.95% for a CI of 95% in our study (Figure 10 and Table 4). The area under the curve is > 0.5 in our study (0.76), which signifies that the FA value of the medulla is a very good and significant test.

Figure 10

Receiver operator curve for medullary fractional anisotropy values for identifying normoalbuminuria

Table 4

Different groups based on the cut-off medullary fractional aniso-tropy (FA) values along with the number of subjects in each group

| Medulla FA value | Control | Diabetics | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 0.4 | 22 | 8 | 30 |

| ≥ 0.377 to < 0.4 | 4 | 13 | 17 |

| < 0.377 | 1 | 52 | 53 |

A summary of the imaging data and t-test results obtained in the entire study is represented in tabulated form (Table 2 and Table 5).

Table 5

Summary of imaging data for all subjects

Discussion

Diabetes is a well-known cause of chronic renal disease. Several changes take place in renal parenchyma architecture in a predictable fashion in diabetic patients because of deranged sugar metabolism. Changes progress from basement membrane thickening, which is the earliest histopathological marker of diabetic nephropathy that can be detected on electron microscopy [20]. Gradually other changes take place, including an increase in the mesangial matrix, Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules sometimes combined with microaneurysms, exudative or hyalinosis lesions, capsular drop, and afferent and efferent arteriolar hyalinosis [21]. However, detection of such pathological changes becomes evident on routine microscopy only in the later course of the disease. Advances in MRI technology, e.g. DTI and DWi, can provide information related to the micro-architecture of an organ, and they have been successfully applied in the brain. ADC and FA values express different characteristics of the same phenomenon, i.e., diffusion. ADC values are mainly affected by the perfusion of the particular tissue, whereas the FA values are a marker of tissue organization that affects the directionality of the water molecules [14]. Of late, the application of these sequences has provided us with the hope of detecting early microstructural changes in diabetic nephropathy in a non-invasive manner, especially in those with normo-albuminuria.

Pathologic changes such as glomerulosclerosis, tubular damage, and interstitial fibrosis, which occur in diabetic nephropathy, lead to a reduction in intercellular space, which restricts the diffusivity of water molecules and subsequently reduces the ADC value. In line with previous studies, we also found that cortical ADC values were significantly lower in diabetic patients than in the control group [22,23]. Analysis of diabetic subgroups in our study revealed that cortical ADC values decreased and were significantly different (one-way ANOVA; p < 0.001) with increasing severity of proteinuria, i.e with increasing renal damage, and were the lowest in diabetics with frank proteinuria. Reduced renal ADC values have been reported in a variety of acute and chronic kidney diseases in many studies [9,24-30].

Renal cortical ADC values were found to be significantly lower in the diabetic subgroup than in controls in a study conducted by Hueper et al. utilizing magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging for the evaluation of histopathological changes in a rat model of diabetic nephropathy [27]. Cortical ADC values were, however, not found to be significantly different between NA and MI, despite there being a significant difference between healthy volunteers and NA, which indicates that there are microstructural changes in NA and MI that are similar but albuminuria has only manifested in the latter.

Since increasing HbA1c and reducing eGFR are indicators of disease progression [31], the cortical ADC followed the predicted direction and showed a strong positive correlation (r = 0.88) with eGFR and a strong negative correlation (r = –0.69) with HbA1c levels. A positive correlation between GFR and renal ADC values along with significantly reduced renal ADC values in impaired kidneys compared with normal kidneys was reported in a study by Xu et al. [32].

Studies conducted in the past have shown conflicting results concerning trends of renal cortical FA in diabetic nephropathy and chronic renal disease [14,28,33]. We found that cortical FA values increased with worsening nephropathy/proteinuria and that there was a significant difference in cortical FA values between healthy volunteers and diabetic subjects (p < 0.001). The values also showed an increasing trend (r = 0.88; strong positive correlation) with HbA1c and a decreasing trend with eGFR (r = –0.86; strong negative correlation). Similar results have been reported by Ahmed et al. [34], who reported that renal FA and ADC in patients with macroalbuminuria (0.43 ± 0.10 and 1.63 ± 0.19 × 10-3 mm2/s) was significantly different (p = 0.001) from that of micro-normoalbuminuria (0.35 ± 0.12 and 1.8 ± 0.18 × 10-3 mm2/s), which is similar to our findings, and that cortical FA values also increased with an increase in the duration of diabetes. They suggested that cortical FA values might help in the differentiation of diabetic kidneys from volunteers. Similarly, Saini et al. [29] in their study found an increasing trend in cortical FA values with increasing level of proteinuria and with reducing eGFR, but unlike our study, they did not find a significant difference in FA values between the microalbuminuric group and those with overt proteinuria. Conversely, in a study by Hueper et al. [27] and Yan [35] et al. done on a rat and a murine model of diabetic nephropathy, respectively, cortical FA was found to be reduced in diabetics; the results are in contradiction with the findings of our study. Similarly, Ye et al. studied 34 diabetic patients and 26 healthy volunteers and found significantly reduced renal cortical values in those with diabetes compared to volunteers [36]. However, no significant difference was found in cortical FA values in diabetics and normal volunteers in a study conducted by Lu et al. [23] while exploring the use of DTI in early changes of diabetic nephropathy.

Reduced cortical ADC and increased cortical FA in diabetics is probably due to the following changes at the cellular level: a) thickening of both afferent and efferent arterioles reduces the vessel diameter, resulting in less perfusion and hence ischaemia-induced diffusion restrictively; b) collagen deposition or sclerosis of the interstitium, which results in reduction of ADC and possible addition to the directionality of diffusion [11,14,27,28,37].

In the renal medulla, the tubules are well organized and arranged radially, due to which it exhibits relatively high anisotropic properties in comparison to the cortex. Also, any disease process that causes alteration in the tubular organization is reflected by a reduction in FA values, which was also seen in our study.

FA values were found to be significantly higher in the renal medulla in comparison to that in the cortex in both the control group and diabetics. The results align with observations made in studies by Lanzman et al. [26] and Hueper et al. [27].

A significant difference was found in the medullary FA values of control subjects and each of the diabetic sub-groups and between diabetics with microalbuminuria and those with proteinuria. We found that FA values of renal medulla showed a declining trend with an increase in renal damage, i.e while moving from controls to diabetics with frank proteinuria, which is similar to studies done by Lu et al. [23], Lanzman et al. [26], Feng et al. [28], and Saini et al. [29]. The declining trend in the FA values in the medulla can be attributed to several models of histopathology that were observed previously: a) tubular atrophy and cellular damage influence the direction of diffusion, as suggested by the rat model [27]; b) collagen deposition and inflammatory cell infiltration also contribute; and c) disruption of normal glomerular filtration membrane structure results in filtering of macromolecular proteins and red blood cells into the tubules, which congest the tubules and impair radial diffusivity, resulting in reduced FA values in the medulla [37,38].

Medullary FA was found to have a positive correlation with eGFR and a negative correlation with HbA1c, which is similar to the results reported by Lanzman et al. [26]. Similar results have also been reported in the study by Saini et al. [29], who concluded that medullary FA was a reliable indicator in detecting early nephropathy changes, especially in diabetics.

Overall, average cortical ADC, cortical FA, and medullary FA values were found to be significantly different between normal healthy controls, patients with eGFR < 60, and patients with eGFR > 60 (p < 0.001). Of note is the presence of significant differences in the cortical ADC, cortical FA, and medullary FA values in controls and diabetics with normo-albuminuria, which establishes that certain microstructural changes are indeed taking place in diabetics in whom nephropathy has not yet manifested clinically and can be detected on MRI. Therefore, these quantitative parameters can be helpful to identify patients with potentially reversible/controllable changes of diabetic nephropathy. Because, among the parameters evaluated in our study, medullary FA has been extensively studied in the past with most studies affirming the use of this parameter to analyse changes of chronic renal parenchymal diseases, we analysed the ROC curve (with AUC = 0.76) to arrive at a threshold to differentiate controls from diabetics with normo-albuminuria, and could achieve a sensitivity of 64% and specificity of 80.95 with use of a medullary FA cut-off value of 0.4.

We acknowledge the following limitations to our study:

the number of subjects is relatively small and the results need to be verified with a larger cohort of diabetics;

we studied only diabetic nephropathy, and other causes of chronic renal diseases were not included;

manual placement of ROI might have caused some degree of subjectivity;

serum creatinine levels and hence eGFR values might be influenced by factors like dehydration, infections, and drugs;

patients on antihypertensive drugs were not excluded, and the use of drugs like diuretic antihypertensives might have caused alteration in perfusion changes, thus affecting some diffusion parameters.

Because studies about DTI and DWI in renal parenchymal diseases seriously differ in their results concerning the parameters studied, there is a need for a prospective study including a sufficiently large group of patients evaluating diabetic patients for changes in diffusion parameters such as FA and ADC of renal parenchyma, to clearly and firmly establish a temporal association of the changes in these parameters and renal function/evolution of diabetic nephropathy.