Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) affects annually 372,000 people worldwide and around 3000 in Poland [1,2]. It is frequently detected in the early stage, usually incidentally in computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR), or ultrasound studies performed due to other reasons.

Partial nephrectomy is the treatment of choice of stage T1 RCC (< 7 cm and no metastases). However, according to European Association of Urology (EUA), European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, patients with T1a RCC who are poor surgical candidates can be treated with percutaneous ablation [3-5]. According to the American Urological Association (AUA), clinicians should consider thermal ablation as an alternate approach for the management of T1a solid renal masses < 3 cm in size [6]. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and microwave ablation (MWA) are the methods that use high temperature to destroy tumour tissue, while cryoablation is a way of killing cancer cells by freezing the tumour.

Out of these 3 methods, cryoablation is gaining a leading position due to several advantages. Firstly, the ablation zone is very clearly visible during treatment under CT guidance. Also, cryoablation can be safely applied in central kidney tumours and in larger lesions; it is also less painful than heat-based methods (RFA and MWA).

Unfortunately, cryoablation of kidney tumours is not widely available for patients in Poland due to lack of reimbursement by the National Health Fund until April 2023. The purpose of this study is to present the results of the first experiences in cryoablation of renal cell carcinoma in Poland. The secondary aim of the study is to find out what results of percutaneous renal tumour cryoablation can be achieved when the operators have no experience in renal ablation or any cryoablation but do have experience in other CT-guided procedures.

Material and methods

The study was accepted by the local bioethical committee (approval number AKBE/84/2024) and was conducted according to Declaration of Helsinki. It involved retrospective analysis of prospectively maintained database of renal tumour cryoablations performed between December 2020 and December 2023.

The patients with RCC in T1a stage (up to 4 cm in diameter) were treated with percutaneous cryoablation. All patients were seen by a urologist and disqualified from surgical treatment due to age, comorbidities, or history of nephrectomy. Exclusion criteria were life expectancy < 1 year, international normalised ratio (INR) > 1.5, and platelet counts (PLT) < 50 k/μl. The stage of the disease was confirmed by baseline CT/MR.

Two patients died within 30 days of the procedure; one in the course of complications of stroke and COVID-19 infection, and one due to a ruptured aortic aneurysm. They were not included in the analysis.

Diagnosis was confirmed by CT-guided core needle biopsy that was performed 2-4 weeks before cryoablation. The biopsies were performed with 18G needles using a coaxial technique (at least 2 tissue samples were taken). In 3 patients no biopsy was done due to history of RCC in the contralateral kidney and enhancement pattern on contrast-enhanced CT typical for RCC.

The cryoablations were done using the IceFX system (Boston Scientific, USA). All procedures were performed under general anaesthesia with CT guidance (320-row CT scanner, Toshiba Aquilion One, Toshiba/Canon, Nasu, Japan). The ablations were performed by 2 of 3 interventional radiologists with at least 10 years of experience in CT-guided ablations. The ablation zone was shaped with multiple needles, so it extended beyond the tumour margin by at least 5 mm.

The following cryoablation protocol was applied: 10 minutes freeze, 1 minute active thaw, 10 minutes freeze, 1 minute passive thaw, and 2-4 minutes active thaw (until needles are removed from the patient). When necessary, hydrodissection was done to separate adjacent organs (e.g. colon, adrenal glands, liver) from the ablation zone and to avoid the danger of thermal injury.

Contrast-enhanced CT was done immediately after each procedure to confirm the size of the ablation zone and to assess for possible complications. In 16 patients contrast-enhanced CT was also done at the beginning of the procedure to improve visibility of the tumour. The remaining 9 patients did not have preprocedural contrast injection due to poor renal function or excellent visibility of the tumour on non-enhanced CT (exophytic tumours).

The follow-up protocol included CT or MR 6 weeks after ablation, then repeated every 3-6 months for a year, and after that once a year.

The following data were collected: patient demographics, tumour characteristics, and course of the procedure. Complications were noted within 30 days of the procedure and classified according to Clavien-Dindo [7]. Follow-up imaging studies were reviewed for complications, local control (defined as lack of enhancement of the ablated tumour), and the presence of metastases.

Results

Twenty-five patients underwent CT-guided percutaneous cryoablation for a T1a RCC. There were 10 females and 15 males among the patients included in the study. The mean age of the patients was 77 years (range: 43-91). The mean diameter of lesions was 27 mm (range: 15-40 mm).

All RCCs were in T1a stage (up to 4 cm in diameter). Three patients presented with RCC in the only kidney (after nephrectomy due to RCC in the contralateral kidney).

The mean number of ablation needles was 3 (range: 2-4), and it depended mostly on the size of the tumour. The needle size was 17G. In one patient, embolisation was performed before cryoablation due to high vascularity of the tumour. Hydrodissection with 100-500 ml of normal saline was carried out in 8 procedures (Figure 1).

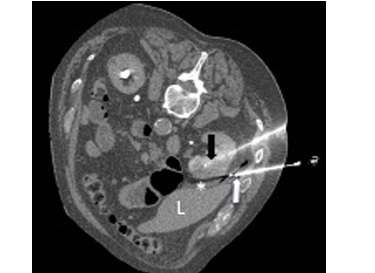

Figure 1

Cryoablation of renal cell carcinoma. Cryoablation needle – black arrow, hydrodissection needle – white arrow, hydrodissection – asterisk, liver – L

The mean duration of follow-up was 12 months (range: 1-30 months). None of the patients presented with local recurrence or distant progression during the follow-up period (Table 1).

Table 1

Demographics, procedure data, and results

Urine leak was noted in one patient, which required stenting of the ureter and subsided within 2 weeks (ClavienDindo grade 3). Otherwise, there were no major postprocedural complications. Minor bleeding was seen in 5 patients, and it subsided in the CT-room within 30 minutes of the procedure, before the patients were transferred to the recovery room (Clavien-Dindo grade 1). None of those patients required intervention or prolonged hospitalisation.

Four out of 25 patients included in the analysis died during the follow-up period. One of them died within 30 days of the cryoablation due to complications after stroke and COVID-19 infection. None of the deaths was directly related to the cryoablation.

Discussion

Thermal ablation (including cryoablation) is included in major urological and oncological guidelines (AUA, EUA, NCCN, ESMO) [3-6] as a method of RCC treatment. It is especially recommended for patients with high surgical risk due to comorbidities, with solitary kidney, compromised kidney function, hereditary RCC, or multiple bilateral tumours [5]. For many years this method has not been available to patients in Poland, mostly due to lack of reimbursement. Our study presents the first experiences of renal cell carcinoma cryoablation in high surgical risk patients in Poland.

One of the major differences between heat-based ablation and cryoablation is the number of needles. There is usually one needle used in RFA/MWA while cryoablation allows the use of multiple needles. This enables to shape the ablation zone to cover the whole tumour at once, even if the lesion is of irregular shape. However, it requires very precise placement of the needles with 1-1.5 cm distance between them; this skill is not necessary in heat-based ablations.

None of the patients presented with local or distant tumour progression (100% progression-free survival). Similar results have been published by Buy et al. [8], who reported recurrence-free survival (RFS) at 96.7% after 28 months, Aoun et al. [9] reported 96.8% at a mean follow-up of 31.8 months, while Breen et al. [10] reported RFS at 97.2% and 93.9% at 3 and 5 years of follow-up, respectively.

One major complication out of 25 procedures (4%) compares favourably with nephron-sparing surgery – 12.6% in the study by Pasticier et al. [11] and 9% according to the American Association of Urology metaanalysis [12]. Similar complication rates were reported by Georgiades et al. [13] and De Cobelli et al. [14].

The results show that a team of interventional radiologists without experience in renal cryoablation but with extensive experience in liver ablation and other abdominal CT-guided procedures can still achieve good results. It shows that interventional radiology procedures should be reimbursed and more frequently applied in oncological patients. This applies even more in elderly patients with comorbidities in whom low complication rates are of high importance. Also, in patients with a solitary kidney, an attempt to perform nephron-sparing surgery could lead to radical nephrectomy followed by permanent treatment with dialysis. The good safety profile of percutaneous cryoablation makes such complications highly unlikely. Also, cryoablation can be repeated in cases of local recurrence or a new tumour.

The limitations of the study include the low number of patients and relatively short follow-up period.