Introduction

Myocardial bridging is defined as an intramural course of an epicardial coronary artery for a variable length. The muscle overlying the tunnelled vessel is called the bridge. The autopsy description of myocardial bridging by Reyman [1] dates to 1732, whereas the first angiographic demonstration was provided by Portmann [2] in 1960. Initially, it was presumed to be benign with favourable long-term outcomes [3]. Subsequently, various clinical syndromes were proposed to be associated with myocardial bridging, including coronary spasm, acute coronary syndromes [4-6], ventricular arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death [7-10], and coronary atherosclerotic plaques proximal to the bridged segment [11]. The prevalence of myocardial bridging varies widely depending on the type of the study, and even the sex distribution varies considerably, with some studies showing either a male or a female predilection and the rest describing an equal prevalence in both sexes [11]. In autopsy series [12-14], the prevalence varies from 20% to 85%, which is substantially higher than that in angiographic studies [15] (0.5-3%); however, when patients with chest pain syndromes and normal coronary angiograms were studied using provocative tests, the prevalence was as high as 40% on conventional angiograms [16,17]. With the advent of multislice computed tomography (CT), CT coronary angiography (CTCA), and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, there has been a paradigm shift in the modality preferred for identifying coronary anomalies, including myocardial bridging; such identification is facilitated by the three-dimensional and multiplanar reformats available with these modalities. As the CT acquisition time is shortened with advanced equipment, motion artefacts are fewer, and myocardial bridging can be identified more accurately, but even with CTCA, the prevalence of myocardial bridging varies considerably from 3.5% to 58% [11,18-20]. This wide variation can be attributed to different generations of CT equipment used in various studies; with quicker image acquisition requiring shorter breath holding times, artefacts and misinterpretations decrease considerably [21]. Another reason could be the ethnicity of the studied population, as observed in an autopsy study [11]. In the present study, we examined the CT prevalence of myocardial bridging and its association with coronary plaques in the Indian population at a high-volume tertiary care centre. Approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee was obtained.

Material and methods

Study population

A total of 4500 individuals who had undergone CTCA for evaluation of chest pain syndromes at our institute were studied for myocardial bridging. Moreover, 100 of them were excluded due to suboptimal imaging secondary to patient characteristics (obesity) and motion artefacts. Data on the clinical profile and indication for CTCA in patients with myocardial bridging were collected. An equal number of age-, sex-, and risk profile-matched controls without myocardial bridging were included in this study, and similar data were collected from them for comparison.

Multidetector computed tomography protocol

CTCA was conducted using 64-slice multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) after patients received 1 ml/kg intravenous iohexol. The scanning area spanned from the tracheal carina to the diaphragm, with patients in the supine position. Only patients with sinus rhythm were included in this study, and the heart rate was reduced to < 80/min using oral metoprolol given one hour before the study. Additional IV metoprolol was used whenever required for better control of the heart rate. ECG-gated images were obtained during breath holding through detector collimation with the following parameters: detector collimation – 64 × 0.625 mm; voltage – 120 kVp; effective mAs of 400-500 mAs; pitch range – 0.2-0.29; gantry rotation time – 0.35 seconds; and slice thickness – 0.6 mm.

Myocardial bridging and coronary plaques

The presence of myocardial bridging was assessed using transverse images and curved multiplanar reconstructed images (Figure 1) when a part of the epicardial coronary artery dipped within the myocardium only to return back to the surface. The total length from the point of deviation from the surface to the point of return to the surface was measured as the length of the bridged segment, and the thickness of the myocardium overlying the bridged segment was measured as the depth of the bridged segment (Figure 2). We assumed the length-to-depth ratio (RA-MA ratio) of the bridged segment as an indirect measure of angulation, with lower values reflecting a more acute angle and vice versa. A coronary plaque is any thickening of the vessel wall with or without narrowing of the lumen, and it is graded into normal, insignificant (< 50% narrowing), and significant (> 50% narrowing).

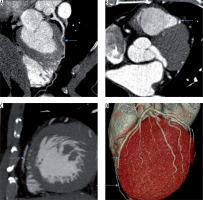

Figure 1

A) Curved multiplanar reformat image showing myocardial bridging of mid left anterior descending artery (LAD) (arrow). B) Transverse image showing myocardial bridging of LAD (arrow). C) Sagittal reformat showing normal epicardial course of distal LAD (arrow). D) Volume rendered image showing myocardial bridging of mid LAD (short arrow) and normal epicardial course of distal LAD (long arrow)

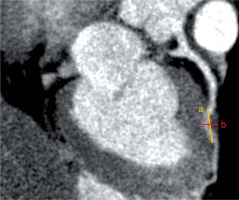

Figure 2

Orthogonal or oblique multiplanar reformatted image in which entry and exit of bridged segment is chosen. Using electronic callipers the distance (a) between the entry and exit point (outer to outer wall of the vessel) of the bridged segment was determined. The shortest distance (b) between epicardial surface and deeper myocardial aspect of the bridged segment was determined. The ratio was derived by using the formula of a/b

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the demographic profile. Patients with and without proximal disease were compared using the χ2 test for ordinal variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Similar tests were used for comparing patients with and without myocardial bridging.

Results

Of the 4400 patients included in the study, 440 had evidence of myocardial bridging, of whom 370 had bridging involving a major epicardial coronary artery, and the remaining patients had bridging involving smaller vessels. Among these 370 patients, 360 had bridging of the proximal to mid left anterior descending artery (LAD) segment, and the remaining 10 patients had bridging of the mid left circumflex artery (LCX). Seventy patients had bridging involving minor epicardial vessels (30 diagonals and 40 major obtuse marginals) that were still larger than 1.5 mm but were excluded from analysis because of proximal segment plaquing. 10.1% (160 of 1590) of women and 9.9% (280 out of 2810) of men had myocardial bridging. As shown in Table 1, baseline characteristics were comparable between these 370 patients with major epicardial vessel myocardial bridging and their matched controls. Based on their age, sex, and type of chest pain, all these patients were evaluated for chest pain syndrome and intermediate pretest probability of coronary artery disease. The prevalence of any or significant atherosclerotic plaque (Figures 3 and 4) in the segment proximal to the bridged segment was 37.8%, which was lower than the prevalence of 48.7% for plaques in corresponding segments among patients without myocardial bridging, who were matched for all other variables (Table 2). Moreover, the prevalence of plaques elsewhere in the coronary arteries was not different between the two groups (patients with and without proximal plaques), reinforcing the appropriateness of matching. The average length of the bridged segment was 15.5 ± 5 mm, and that in patients with and without proximal plaques was 13 ± 4 and 16 ± 6 mm (p = 0.1), respectively. Similarly, the average depth of the segments with and without proximal plaques was 1.8 ± 0.6 mm and 1.4 ± 0.5 mm (p = 0.06), respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups, whereas the RA-MA ratio (8 ± 3 vs. 13 ± 6, p = 0.01) was significantly lower in patients with atherosclerotic plaques. In univariate analysis, age and the presence of diabetes were also significantly associated with the presence of plaques proximal to the bridge among patients with myocardial bridging. In multivariate analysis, only age was found to be significant.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics

Table 2

Prevalence of proximal segment plaque among cases and controls

| Proximal vessel | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Insignificantdisease | Significantdisease | ||

| Cases | 230 (62.2%) | 80 (21.6%) | 60 (16.2%) | 370 |

| Controls | 200 (51.3%) | 130 (33.3%) | 60 (15.4%) | 390 |

| Total | 430 | 210 | 120 | 760 |

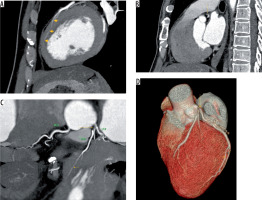

Figure 3

A) Sagittal reformat image showing myocardial bridging (arrows) of left anterior descending artery (LAD) involving a long segment. B) Sagittal reformat image showing coronary artery disease (arrow) in segment proximal to bridging in the same individual as in a. C) Reformat image showing myocardial bridging (short arrow) of LAD involving a long segment with coronary disease (long arrow) in the segment proximal to bridging in the same individual as in a. D) Volume rendered image showing myocardial bridging (short arrow) of LAD involving a long segment with coronary disease (long arrow) in the segment proximal to bridging in the same individual as in a

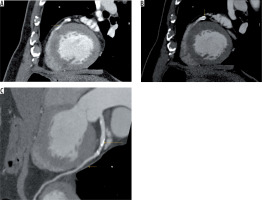

Figure 4

A) Sagittal reformat image showing myocardial bridging (arrow) of left anterior descending artery (LAD) involving a short segment with coronary disease in the segment proximal to bridging. B) Sagittal reformat image showing coronary artery disease (arrow) in the segment proximal to bridging in the same individual as in a. C) Reformat image showing myocardial bridging (short arrow) of LAD involving a short segment with coronary disease (long arrow) in the segment proximal to bridging in the same individual as in a

Discussion

In this study, the 64-slice MDCT prevalence of myocardial bridging among this cohort of Indian patients with chest pain syndromes and intermediate pretest probability of CAD was 10%, which is lower than the prevalence in other studies [22]. We presume the lower prevalence to be secondary to ethnicity because this is the first CT-based study to evaluate the prevalence among Indian patients. Moreover, we included only cases with definite evidence of bridging and excluded equivocal cases and those suggestive of motion artefacts. This led to higher specificity and lower sensitivity and hence lower prevalence. Finally, bridging involving vessels less than 1.5 mm in diameter was excluded because the mural course of these vessels may be considered normal even otherwise. Male and female patients were equally affected in our study, which is similar to the observation in other studies [11]. Similar to other studies, in this study, the most common vessel involved was LAD, and mid-LAD was the most common segment [22, 23]. Plaquing of the segment proximal to the bridged segment and the protection of the bridged segment were attributed to the shear stress on the endothelium caused by blood flow, which was considered lower than normal for the bridged segment and higher for the proximal segment. This shear stress can be presumed to be proportional to the amount of systolic deformation and its persistence in diastole, which in turn is dependent on the length, depth, RA-MA ratio, and myocardial contraction. We propose that a smaller RA-MA ratio indicates sharper angulation than a longer or a deeper segment alone can predict. In support of this, our study showed that the RA-MA ratio was significantly lower in patients with proximal plaquing than in patients without proximal plaquing, whereas the length or the depth of the bridged segment alone was not significantly different between these two groups. However, in multivariate analysis, only age was significantly associated with proximal segment plaquing. Diabetes and the small length-to-depth ratio of the bridged segment became nonsignificant in multivariate analysis. In addition to the length and depth, this simple ratio (RA-MA ratio) may be an additional parameter in risk assessment of myocardial bridging. More complex parameters such as transluminal attenuation gradient are also emerging [24].

Limitations

The limitations of our study include its retrospective and case-control nature. Because the number of patients with bridging was small, the power of the study was lower. The degree of systolic deformation of vessels was not assessed in our study, which would be more correlative with the presence of a proximal segment plaque. Finally, a study cohort with chest pain syndromes will be different from the general population, limiting the extrapolation of this prevalence to the general population. The haemodynamics of blood flow in the tunnelled and proximal segment determined using intravascular Doppler ultrasound as a function of the length, depth, and their ratio on CTCA may provide insights into the anatomic grading of bridging and its physiological effects on the coronary plaque [25].

Conclusions

The MDCT prevalence of myocardial bridging in our population with chest pain syndromes was 10%, with mid-LAD being the most common segment involved. Proximal segment plaquing was associated with age, presence of diabetes, and lower RA-MA ratio of the bridged segment in univariate analysis, but only age retained significance in multivariate analysis. We conclude that coronary plaques in LAD are similar in patients with and without myocardial bridging, and although a lower RA-MA ratio of the bridged segment influences proximal segment plaquing, it is not over and above what can be explained by patient age alone.