Introduction

Lower limbs are rarely involved in arterial injuries; traffic- related trauma and iatrogenic lesions during orthopaedic surgical procedures represent the main causes [1]. Haemorrhagic or ischaemic symptoms are the main clinical manifestations of these injuries.

Surgery has been the reference treatment in the management of vascular extremity injuries for many years [2,3]; recently endovascular techniques have been shown to be as effective as open surgery, and currently their use is increasing for the treatment of these injuries [1]. This is based on the continuous improvements in technology provided by the biomedical industry, which allow easy identification of the vascular lesions without general anaesthesia, lower hospital.

This paper focuses on the role of interventional radiology embolisations in a series of patients presenting with iatrogenic vascular injuries of the lower limbs following orthopaedic interventions.

Preprocedural imaging is crucial: contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) with thin slices and multipurpose reconstructions plays a pivotal role both in lesion diagnosis and procedural planning to choose the technique and materials.

In the literature this scenario has been reported mainly in the form of case reports concerning vascular complications of a specific orthopaedic intervention [4-14]; this paper aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy of endovascular embolisation in a series of patients presenting with arterial injuries of the lower limbs following orthopaedic surgery.

Material and methods

This is a single-centre retrospective analysis of data collected in a tertiary care centre; data has been extracted from a local electronic database. Written, informed consent was obtained from all patients.

In nine years 14 patients have been treated with endovascular arterial embolisation for iatrogenic vascular lesions occurring after orthopaedic surgery of the lower limb. Inclusion criteria for endovascular treatment were: CT signs of arterial injury in patients having haemoglobin value reduction and/or pain and reduced limb motion after orthopaedic surgery. If the CT did not report any arterial injuries, patients did not undergo to angiosuite.

All patients responding to the abovementioned criteria were treated with endovascular procedures during the time considered in this sample.

There were six males and eight females, with a mean age of 64 years, ranging from 23 to 90 years.

The orthopaedic surgical interventions were as follows: gamma nail positioning after intertrochanteric femoral fracture (3), cemented total hip arthroplasty (4), non-cemented total hip arthroplasty (2), anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (1), femoral stabilisation with metallic plate and screw fixation after displaced diaphysis fracture (2), stabilisation of a tibial lateral condyle fracture (1), and tibial stabilization with Ilizarov fixation after displaced diaphysis fracture (1) (Table 1).

Table 1

Population data: age, sex, orthopaedic intervention, and clinical presentation

Clinical presentations consisted of palpable pulsatile mass, painful and reduced lower limb motion, or visible haematoma; 11 patients presented also with anaemia (haemoglobin < 7 g/dl).

All data analyses were performed in a MATLAB environment (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts).

Results

The time between orthopaedic surgery and embolisation ranged between 0 and 67 days (mean: 15 days).

Overall, 16 vessels were injured; in two patients there were two vessels involved, while in 12 cases there was a single vessel injured.

The injured arterial vessels were as follows (Table 2): inferior gluteal artery (2), superficial external pudendal artery (2), deep femoral artery (1), lateral circumflex femoral artery (Figure 1) (3), medial circumflex femoral artery (2), articular branch of descending genicular artery (1) (Figure 2), perforating femoral arteries (3), posterior tibial recurrent artery (1), and anterior tibial artery (1) (Figure 3).

Table 2

Results data: interval time between orthopaedics surgery and embolisation, number of vessels injured, artery involved, typology of arterial injury, embolising agent

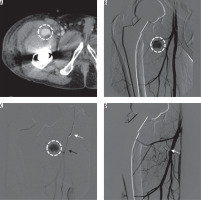

Figure 1

60-year-old man, 35 days after cemented total hip arthroplasty and presenting with groin swelling and bleeding pseudoaneurysm of the right lateral circumflex femoral artery. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) in axial plane (A) showed a 2.4-cm pseudoaneurysm (white dotted circle) in the right groin region. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) in anteroposterior projection (B) confirmed the lesion (white dotted circle), recognising the arterial supply from a branch of the deep femoral artery, the lateral circumflex femoral artery. With a coaxial technique (C), using a 5 Fr multipurpose catheter (white arrow) and a 2.7 Fr microcatheter Progreat Terumo® Japan (black arrow), the vessel was superselectively catheterised and then embolised with pushable microcoils (Tornado, Cook Medical®, USA). The final DSA run (D) confirmed the technical success with exclusion of the lesion from the arterial flow (white arrow indicates the microcoil cast)

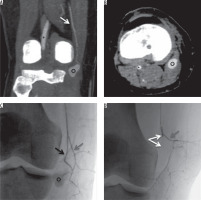

Figure 2

23-year-old man with complete lesion of the right anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) occurring during a football match; three months later he underwent ACL reconstruction without intraprocedural complications. During the postoperative period he referred a pulsatile mass without pain in the medial side of the popliteal cavity. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) detected an 18-mm pseudoaneurysm refurnished from the articular branch of the descending genicular artery. The lesion was successfully excluded from blood flow and the pulsatile mass disappeared shortly after embolization with a microplug (MVP 3, Reverse Medical®, Irvine, CA, USA). Contrast-enhanced CT in coronal (A) and axial (B) planes showing intra-articular segment of popliteal artery (black asterisk), descending genicular artery (white arrow), and pseudoaneurysm (black circle). Procedural fluoroscopy in posteroanterior projection (C, D): 2.7 Fr microcatheter positioned into the distal portion of descending genicular artery; only the articular branch (black arrow) refurnishes the pseudoaneurysm (black asterisk) and has been occluded with a microplug (bifurcated white arrow) while the saphenous branch (grey arrow) has been preserved from embolisation

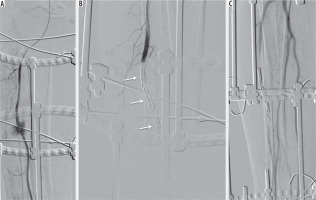

Figure 3

53-year-old male with Ilizarov fixation of the right tibial diaphysis for a displaced fracture after a motorbike accident; the patient presented with swelling of the anterior portion of the leg, pain, haematoma, and anaemia two days after orthopaedic surgery. Echo colour Doppler showed a haematoma actively refurnished from the anterior tibial artery. The angiography confirmed bleeding; therefore, complete occlusion of the anterior tibial artery was performed with microcoils (MicroNester CookMedical® USA), including the arterial segment before and after the bleeding source. The patient was not vasculopathic, peroneal and posterior tibial artery patency was assessed before. Posteroanterior angiography projection (A) showing active bleeding (black circle) from the middle third of the anterior tibial artery; Ilizarov fixation is also appreciable. Complete occlusion of the anterior tibial artery with multiple microcoils (white arrows) (B) with consequent bleeding interruption as confirmed by the final angiographic control (C) with patency of the posterior tibial and peroneal arteries

The vascular lesions were as follows: pseudoaneurysm (57%), bleeding with extraluminal contrast agent blush of the terminal arterial segment (36%), and laceration and bleeding with extraluminal contrast agent blush of the arterial main trunk (7%).

The embolisation procedures have always been performed with a femoral access, contralateral to the injured vessel; under ultrasound guidance a 5-French introducer was positioned; only in the case of stent graft implantation a larger sheath was required, otherwise all the procedures were conducted with a 5 French access.

A 5 French diagnostic catheter was positioned in cross-over into the ilio-femoral limb of the injured vessel and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) with antero-posterior, and oblique projections were acquired to confirm the CT scan diagnosis; oblique projections are also essential to displace metallic prosthetic elements from the field of view. Then, a 2.7 French microcatheter was adopted to reach distally the lesion and to embolise. Finally DSA runs confirmed the procedural success. The femoral access was closed with mechanical devices (Femoseal or Angioseal 6 VIP, Terumo®, Japan) and an elastic patch.

The embolising agents adopted (Table 2) were as follows: microcoils 57%, glue 14%, microplug 7%, particles 14%, and covered stent 7%.

Technical success was achieved in all cases (100%) with pseudoaneurysm occlusion and bleeding interruption. No major complications were registered; two minor complications occurred (CIRSE Classification System for Complications: Grade 1) [15], consisting of groin haematoma in the site of femoral access not requiring medical treatment.

Patients suffering from anaemia showed progressive improvement on haemoglobin values, reaching physiological ranges during the hospital stay; patients with pseudoaneurysms presenting as pulsatile mass immediately referred disappearance after the intervention, as confirmed by echo colour Doppler scans.

Discussion

Vascular complications after orthopaedic surgery of the lower limb are rare but can be limb-threatening and sometimes even life-threatening events.

Vascular lesions during knee arthroscopy are responsible for less than 1% of all complications from these procedures [5]. Total knee replacement is a common orthopaedic procedure with more than 600,000 interventions performed each year in the United States and with reported incidence of vascular complications of 0.3-1.6% [16]. Similarly, vascular injuries during hip arthroplasty occur in up to 0.2% [17]; this is due to wide arterial network of this anatomical region.

The number of vascular complications, even if still a low percentage, increases in absolute numbers as the techniques generalise, especially concerning arthroscopic and prosthetic interventions related to the population aging trend.

For these reasons, the Hip Society [18] and the Knee Society [19] have standardised the list and definitions of complications in course of surgery for total hip and total knee arthroplasties, contemplating, among others, vascular injuries.

In this scenario, different types of vascular complications have been reported in medical literature, mainly in the form of case reports: vessel laceration, haemorrhage, vascular compression, intimal flap tear, pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous aneurysm, arterial thromboembolism, and ligation [4-14,20].

Several factors can produce the vascular injury, from direct perforation by an instrument (such as retractor, screw, or scalpel) to chronic and slow erosion of a vessel (by protruding screws, migration of a loose component) or indirect injury resulting from stretching of atherosclerotic or calcified arteries or thermal damage from the polymerisation of cement near to a blood vessel [21].

Underlying vascular diseases are commonly accepted as identifiable risk factors for arterial insufficiency that can lead to wound complications and periprosthetic joint infection; furthermore, patients receiving anticoagulants, such as subcutaneous heparin, take longer to seal traumatised vessels and are more likely to experience prolonged bleeding.

Lesions can be diagnosed intraoperatively, or days to years after the surgery; patients may present with pain, swelling, bleeding, ischaemia, or a combination of these symptoms [14].

Based on clinical examination, instrumental diagnosis is primarily done via ultrasound scanning, especially in the case of pseudoaneurysms showing flow outside the artery, the presence of a track from the puncture site to the aneurysm sac, and a ‘to and from’ flow pattern corresponding to filling and emptying of the sac during systole and diastole, respectively; contrast-enhanced CT and angiography can be used for optimal decision making, also in the case of limb lesions [10,22].

The treatment depends on the type, size, and location of the vascular lesion. Interest in endovascular procedures has risen in the last two decades because it has proven to be efficient for diagnosis and treatment contextually by direct embolisation using liquid or metallic agents; stent grafts could also be used because this has become a valid alternative to open repair, although the use of stent grafts across highly mobile joints should be avoided. Open surgical repair is reserved for cases that cannot be managed by endoluminal approaches and need thrombectomy, oversewing, ligation, arterial wall repair by patch, vein graft, or arterial bypass [23]; furthermore, it should be taken into account that surgical repair is usually associated with increased morbidity and longer hospital stay [6].

In accordance with literature data, the most frequent lesions faced in this sample were pseudoaneurysms, which have been ultimately treated mainly by microcoils. This is because microcoils can be safely deployed distally thanks to superselective microcatheterisation [24]; furthermore, detachable coils allow a safe approach even for lesions located in the proximity of vessel bifurcations that have to be spared with controlled release and possible repositioning. In one case, a microvascular plug was adopted; this is a recently developed embolising device [25,26] that seems to be promising for occluding small vessels with a straight course, such as limb arteries, because it requires a landing zone of almost 12 mm.

This study presents some limitations. First of all, a small number of patients were enrolled, but this was a single-centre study on rare lesions. Also, different orthopaedic interventions on multiple sites of the lower limb were taken into account, and so the sample could appear inhomogeneous. However, the aim of the study was not to focus on a single orthopaedic intervention but instead on the safety and efficacy of endovascular embolisations in lower limb arterial iatrogenic injuries.

Conclusions

Endovascular embolisation is a safe and effective approach to treat vascular lesions occurring after different orthopaedic interventions of lower limbs in this series; orthopaedic surgeons should be aware of the support that interventional radiologists could provide in the case of vascular complications.