Introduction

Tuberculosis is quite common in India. About 40% of all Indians are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with 2.5 million active tuberculosis cases [1]. Tuberculosis primarily affects the lungs, but it can affect any organ. Extra-pulmonary involvement occurs in 15-20% of immuno-competent patients and in more than 50% of those with HIV infection [2]. The most common extra-pulmonary sites are lymph nodes, pleura, abdomen, genitourinary tract, skin, joints and bones, or meninges. In this pictorial review article, we present 8 atypical cases of tuberculosis and describe their imaging features and histopathology. Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis can affect virtually any organ and can mimic various inflammatory and neoplastic disorders apart from infective conditions. Strong index of clinical suspicion is required, particularly in countries endemic to tuberculosis.

Case reports

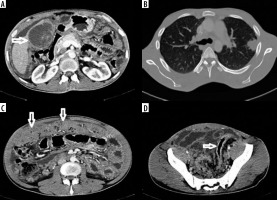

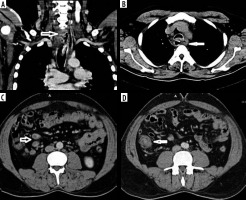

Gallbladder tuberculosis

A 24-year-old male presented with insidious abdominal pain and weight loss for 4 months. Ultrasound revealed enlarged gallbladder with wall thickening and mild ascites. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) showed enlarged multi-cystic lesion replacing gallbladder with ascites, ‘omental caking’, and minimal recto-sigmoid colonic wall thickening. CT of the thorax revealed multiple air-space opacities in left upper lobe with mediastinal, hilar, para-aortic, and peri-pancreatic lymph adenopathy. A few nodes showed calcifications/central necrosis (Figure 1). The differential diagnoses considered included disseminated gallbladder malignancy and disseminated tuberculosis with gallbladder involvement (due to the young age of patient and calcified lymphadenopathy). The patient underwent cholecystectomy with biopsy diagnostic of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis of the gallbladder is rare, and preoperative diagnosis of gallbladder tuberculosis is difficult [3]. Three main types of gallbladder tuberculosis are described: micro-nodular or polypoidal type, mural thickening type (most common, and may also present as halo due to peri-cholecystic oedema), and mass-forming type [4]. Rarely, multi-cystic form has been described. A recent review found only about 120 cases reported in world literature to date [5]. The differential diagnosis includes gallbladder malignancy or xantho-granulomatous cholecystitis. The presence of co-existing pulmonary tuberculosis, calcifications in the gallbladder wall, and calcific/necrotic lymph adenopathy all point to a diagnosis of tuberculosis. The unusual features of this case include multi-cystic variant, peritoneal involvement, and absence of hepatic granulomas.

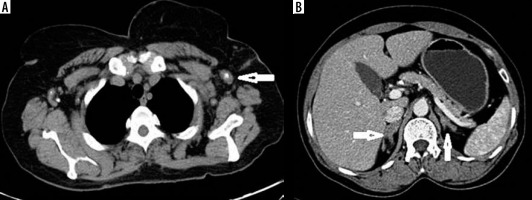

Hepato-biliary tuberculosis

A 50-year-old woman presented with insidious onset of jaundice, without any history of fever or biliary colic. Ultrasound (USG) revealed multiple tubular echogenic structures communicating with the biliary system. The gallbladder was normal. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and CECT revealed irregularly dilated bile ducts with ill-defined hilar mass, multiple strictures, and enhancement involving the common bile duct (CBD) wall (Figure 2). Multiple peri-pancreatic, para-aortic lymph nodes were also noted with minimal ascites. The ileocecal junction and lungs were also normal. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) revealed features of tuberculosis. This was a case of primary biliary involvement without pulmonary or hepatic tuberculosis. Four major types of hepato-biliary tuberculosis occur: miliary type, tuberculomas, abscesses, or biliary involvement, of which biliary tuberculosis is rare, with only about 20 cases reported in the literature [6]. The mode of spread is haematogenous or local contamination (bowel, adjacent lymph nodes, or hepatic granulomas). Intra- and extra-hepatic bile ducts are involved with dilatation and stricture formation. Lobar atrophy with capsular retraction has also been reported. Multiple strictures may occur, mimicking primary sclerosing cholangitis/cholangiocarcinoma. In their review of imaging findings of 71 previous reports of hepatobiliary tuberculosis, Karaosmanoglu AD mentioned hepatic granulomas and peri-portal lymphadenopathy as other features [7].

Figure 2

A) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography axial section shows dilated intrahepatic biliary radicles with enhancing wall thickening and internal heterogeneity. T2-weighted image axial and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography images reveal dilated bile ducts (A) with common bile duct strictures (B)

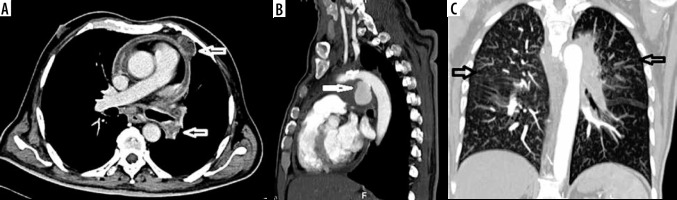

Oesophageal tuberculosis

A 39-year-old male patient presented with gradually progressive dysphagia to solids and liquids with weight loss and altered bowel habits. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed circumferential thickening of mid-oesophagus about 10 cm from the cricopharynx with multiple ulceroproliferative lesions. CECT revealed long segment wall thickening of the upper oesophagus, along with perio-esophageal peripherally enhancing nodes with necrotic centre. A few conglomerated lymph nodes were also noted in the paratracheal region with infiltration into the oesophageal wall causing ulceration. There was also short segment ileocecal wall thickening with necrotic mesenteric, para-aortic lymph adenopathy, and large conglomerated necrotic peri-pancreatic nodal mass (Figure 3). There was no evidence of pulmonary involvement. Oesophageal tuberculosis is relatively rare and is almost always secondary (mediastinal lymph adenopathy/pulmonary or spinal tuberculosis) [8]. Presence of necrotic lymph adenopathy, fistulous tracts, mid-oesophageal involvement, and tuberculosis elsewhere can be of help to the diagnosis. In a recent review of clinical and endoscopic features, Xiong et al. reported only 14 cases of oesophageal tuberculosis [9]. The salient features of this case were absence of pulmonary tuberculosis, ulceration, and communication between oesophageal wall and necrotic node along with co-existent ileocecal tuberculosis.

Figure 3

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) sections show eccentric wall thickening of proximal oesophagus with ulcerations (A) and ‘double-lumen sign’ (communication between oesophagus and necrotic paraoesophageal node) (B). C-D) CECT axial sections show necrotic lymph nodes and ileocecal thickening (arrows)

Tuberculous aortitis

A 62-year-old man presented to the emergency with non-productive cough for 3 weeks and acute onset severe chest pain. Aortic dissection was suspected clinically, and CT angiography was done to rule out dissection, which revealed an irregular lobulated 3.3 × 3.5 × 3.7 cm (trans × AP × CC) pseudo-aneurysm encased by an irregular peripherally enhancing soft tissue (Figure 4). The rest of the aorta and its branches were normal. There were multiple necrotic peripherally enhancing lymph nodes in the mediastinum (bilateral hilar, para-aortic/aorto-pulmonary, and para-tracheal). Lung window revealed multiple centrilobular and “tree-in-bud’ nodules along with minimal pericardial effusion and mild pericardial thickening. Screening of the abdomen revealed small hypo-enhancing splenic nodule and uniformly enlarged bilateral adrenal glands. Based on clinical and imaging features the possibility of tuberculous aortitis was considered. Tuberculous aortitis is extremely rare and is usually secondary to local infiltration (mediastinal lymph adenopathy or vertebral cold abscess) or haematogenous spread (unlikely) [10]. Pseudo-aneurysm develops secondary to infective aortitis causing weakening of the aortic wall. It is a form of contained leak, which, if it ruptures, can be uniformly fatal. Common sites are distal aortic arch and descending aorta [11]. In a report of tuberculous aortic pseudoaneurysm with vertebral TB, Xue et al. found 22 cases reported in the literature [12].

Figure 4

A) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows pericardial thickening/effusion with necrotic hilar and mediastinal lymph adenopathy (arrows in A). B) Sagittal computed tomography angiography reveals pseudo-aneurysm at the aortic isthmus. C) High resolution computed tomography thorax maximum intensity projection image reveals multiple centrilobular and “tree-in-bud” nodules in both lungs

Adrenal tuberculosis

A 51-year-old male smoker was evaluated for Addison’s disease. Adrenal CT protocol was done to rule out adrenal pathology, which revealed enlarged hypo-enhancing nodular bilateral adrenal glands with preserved adrenal contour. Absolute and relative wash-out indices were 50% and 24%, respectively, ruling out adenoma. There were also multiple axillary, mediastinal, and intra-abdominal lymph nodes, a few of them showing dystrophic calcification (Figure 5). Bilateral lung fields revealed mosaic attenuation along with inter- and intra-lobular septal thickening (bilateral posterior basal segments), honeycombing changes, and a few larger lung cysts suggestive of interstitial lung disease. The adrenal lesion was subjected to CT-guided biopsy, which was suggestive of tuberculosis. Adrenal tuberculosis is present in about 6% of patients with active tuberculosis [13]. In the active phase, bilateral adrenal enlargement with preserved contour, central non-enhancing areas (caseous necrosis), and central “dot”-like calcifications are seen. Later, atrophy and dystrophic calcifications occur. Adrenal tuberculosis is the most common cause of Addison’s disease in endemic countries, while the autoimmune form is described as common in western literature [14]. The features of bilateral enlarged adrenals with preserved gland morphology and calcifications suggesting the diagnosis of tuberculous rather than autoimmune aetiology [15]. Adrenal histoplasmosis is indistinguishable from tuberculosis on imaging. Adrenal lymphoma may also mimic tuberculosis, but calcification is seldom seen.

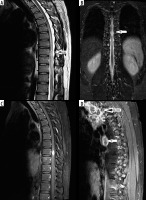

Spinal cord tuberculosis

A 30-year-old male, recently diagnosed as a case of tuberculosis with lung nodules and mediastinal/cervical nodes, presented with progressive asymmetrical paraplegia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done to rule out Pott’s spine. Long segment T2/short tau inversion recovery (STIR) hyperintensity was noted involving thoracic cord from T5-T6 level to T12 level, with a well-defined intra-medullary oval lesion along the long axis of cord. The lesion was isointense on T1W1, iso-hypointense on T2WI, and with intense rim enhancement on post-contrast images. There was no leptomeningeal enhancement or clumping of nerve roots. Multiple peripherally enhancing conglomerated mediastinal lymph nodes were noted on post-contrast T1WI (Figure 6). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) evaluation showed lymphocyte predominance. Based on imaging and clinical history, a diagnosis of intra-medullary spinal tuberculosis was made and the patient was started on anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) and steroids (for the initial phase). After a period of initial worsening, the patient improved, confirming the diagnosis. Intra-medullary tuberculosis is rare with reported incidence of about 2 per 1000 central nervous system (CNS) tuberculosis cases [16]. The various types of spinal tuberculosis are tuberculous spondylodiskitis (most common), tuberculosis myelitis/intra-spinal tuberculomas, leptomeningitis, arachnoiditis, and epidural abscess. Intra-medullary tuberculomas are usually secondary to haematogenous spread and manifest radiologically as 3 stages. In the early stage the lesion appears T1 and T2 isointense with uniform nodular enhancement and intense oedema. With caseation and formation of the wall, T2 hypo-intensity develops with rim enhancement. In later phases “target sign” develops on T2WI as liquefaction of central liquefaction necrosis producing hyperintensity surrounded by hypointense rim [16]. The presence of rim enhancement/target sign and low T2 signal are suggestive of tuberculomas. In tuberculous arachnoiditis, CSF loculations with loss of cord outline in the cervicomedullary region and clumping of lumbar nerve roots (arachnoiditis) are seen with nodular leptomeningeal enhancement [17].

Figure 6

A-B) Sagittal-T2-weighted and coronal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) images at thoracic cord level show long segment T2/STIR hyper intensity with intra-medullary mass lesion at T9 level (arrows). C-D) Post-contrast T1-weighted sagittal images showing ring-enhancing lesion in thoracic cord with conglomerate necrotic mediastinal lymphadenopathy (D)

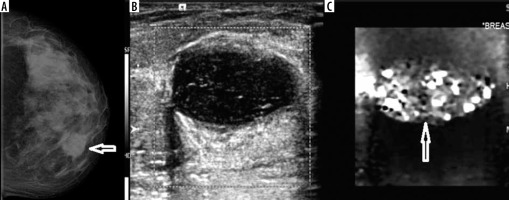

Tuberculous mastitis

A 49-year-old female patient presented with a lump in her left breast. On examination, a firm mass was palpable in the left breast inner quadrant. Mammogram revealed dense breasts with a circumscribed dense mass in upper-inner quadrant of left breast about 4 cm from the nipple-areolar complex. There were no intralesional macro/micro-calcifications. There were multiple axillary lymph-nodes, the largest of which measured about 1.5 cm in the short axis. On USG, the lesion was oval shaped, with thick walls (broader than tall morphology), hypoechoic with few septations, adjacent fat inflammation, and posterior acoustic enhancement. There was no internal vascularity noted and the lesion was soft on elastography (Figure 7). Fine-needle aspiration cytology revealed features of chronic inflammation suggestive of tuberculosis. Tuberculous mastitis is rare and commonly seen involving the upper outer quadrant of the breast. Its mode of spread has been suggested to be direct inoculation (rare), haematogenous, or lymphatic spread from primary focus. Five types of presentation of tuberculosis are described: nodular (most common type), disseminated, sclerosing (with caseation and fibrosis causing nipple retraction mimicking malignancy), tuberculous mastitis obliterans, and miliary tuberculosis [18]. A recent study from South Africa by Mathew et al. using ultrasound and mammography used slightly different classification: abscess, inflammatory/disseminated, lymphadenitis, nodular, and sclerosing forms [19]. Complications include ulceration leading to formation of sinuses/fistula and fibrosis (so-called ‘frozen breast’) [20]. Our patient would fit into the solitary nodular type. The soft nature on elastography along with posterior acoustic enhancement prompted us to suggest benign aetiology rather than malignancy. The unique features of our case were location (inner quadrant) and absence of tuberculosis elsewhere.

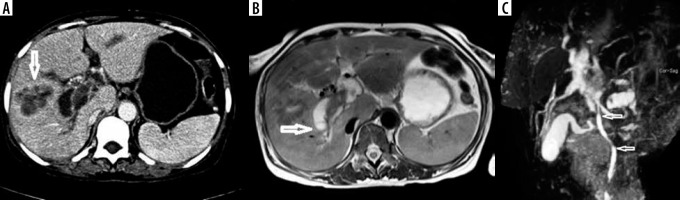

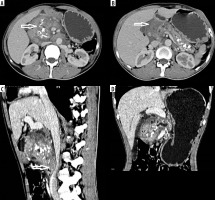

Pancreatic tuberculosis

A 45-year-old male, an alcoholic with recurrent history of abdominal pains, presented with acute onset of abdominal pain and cough. CECT of the abdomen and thorax revealed an enlarged heterogeneously hypodense, hypo enhancing infiltrative lesion involving the head and body of the pancreas, with intra-pancreatic cystic lesions and peri-pancreatic fat stranding. Coarse pancreatic calcifications were noted, suggesting a background of chronic pancreatitis. Loss of fat planes with the second part of duodenum and superior mesenteric vessels was noted with compression of the superior mesenteric vein and IVC (Figure 8). Mild dilatation and wall enhancement of biliary radicles, CBD, and MPD were noted along with multiple enlarged hypo-enhancing peri-pancreatic, para-aortic lymph nodes and uniformly enlarged left adrenal gland. ‘Tree-in-bud’ nodules were noted involving left lung lower lobe, suggestive of endo-bronchial tuberculosis. As imaging features were equivocal for malignancy, patient underwent surgical resection of Whipple’s procedure. The histopathological diagnosis was of tuberculosis on a background of chronic pancreatitic changes. The odd features of our case include the presence of endo-bronchial, adrenal tuberculosis, vascular compression and co-existing chronic calcific pancreatitis. Tuberculosis of the pancreas is very rare, with an incidence rate of < 1/300 abdominal tuberculosis cases, with very few reports of primary pancreatic tuberculosis [21]. Clinical presentation and imaging features are non-specific. On USG, focal or diffuse pancreatic enlargement with cysts are reported. On CT, infiltrative mass, multi-loculated cystic lesions, and necrotic and low attenuating micro-nodules < 1 cm (particularly in HIV patients) are reported [22,23]. CT has the advantage of revealing associated findings such as peri-pancreatic inflammation, lymph adenopathy, bowel wall thickening, hepatic/splenic nodules, and ascites. Most of cases have another focus of pulmonary/extra-pulmonary tuberculosis. In the presence of isolated pancreatic tuberculosis, HIV infection or other predisposing causes should be ruled out because pancreas is considered inherently resistant to mycobacterial seeding due to pancreatic enzymes [24]. The pancreatic head-neck region is the most commonly reported location [25]. Pancreatic TB is classified radiologically into 3 groups: mass-forming, diffuse, and micro-modular types, with mass-forming being the most common type. USG/CT or endoscopy-guided FNAC may provide less invasive means of diagnosis. The differential diagnosis includes chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic adeno carcinoma, cystic pancreatic neoplasms, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis [26].

Figure 8

Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (A-B) images showing infiltrative mass in head of pancreas, pancreatic calcifications, and cysts. CECT sagittal and coronal reformation (C-D) image showing infiltrative pancreatic head mass causing focal stenosis of Inferior vena cava and pancreatic duct dilatation

Discussion

Tuberculosis, although primarily a disease of the lungs, can involve any organ in the body with or without primary pulmonary involvement. In the industrialized world, extra-pulmonary tuberculosis is reported mostly in HIV patients, but none of our patients were HIV positive [27]. Of our patients, 2 (25%) were female and 6 (75%) were male, with an average age of 43.8 ± 11.5 years. Four patients (50%) had evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis, one had disseminated tuberculosis, and one had co-existing ileocecal tuberculosis. All patients had co-existing lymph adenopathy, thus concurring with other Indian studies [2]. The mode of transmission is predominantly through droplets. The typical pathological features include granulomas with central caseous necrosis surrounded by fibroblasts, epithelioid cells, Langhans giant cells, and lymphocytes. There is an abundance of giant cells/inflammation in the early phase, while thick collagenous capsule forms later. Dystrophic calcification of caseous material is a hallmark of chronic tuberculosis. Sarcoidosis is a classic mimicker of tuberculosis pathologically, while Wegener’s and Churg-Strauss, fungal and histoplasma may also closely mimic tuberculosis pathologically [28]. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) positivity depends on the bacillary load of the specimen and the type of material. Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis is mostly pauci-bacillary, and hence DNA amplification techniques may be needed [29]. AFB could not be detected in any of our specimens. The predominant radiological features in extra-pulmonary tuberculosis include dystrophic calcifications, necrotic lymphadenopathy, strictures, cystic areas, micro-nodules, and fistula formation. On T2W1 (hypointensity caseation, hyper intensity abscess/oedema) varying signal intensities with irregular rim enhancement has been described. However, tuberculosis cannot be distinguished from malignancy radiologically, and hence pre-operative/pre-histopathological diagnosis may not be possible in many cases. Although imaging suggested the possibility of tuberculosis in 5/8 cases (62.5%), it excluded tumours only in 2/8 cases (25%).

Conclusions

Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis is common, particularly in endemic countries. Radiologists as well as clinicians need to be aware of the imaging features and atypical sites of tuberculosis. A thorough radiological evaluation may suggest a possibility of tuberculosis and uncover additional sites of involvement, and CT is preferred modality. Considerable overlap exists between imaging features of tuberculosis and other disorders, in particular malignancy, and only histopathology can provide the final diagnosis with certainty.